December 10

Between this date in the year 112 A.D. and December 9, 113 A.D. was cut the inscription which appears at the base of the majestic column erected in Rome to perpetuate an account of the Dacian wars of 101–06. The shaft of the monument rises 97½ feet, and is surmounted bv a statue of St. Peter. The column has a spiral band which in twentythree turnings, from the bottom to the top, contains a sculptured frieze 3½ feet wide and 800 feet long, depicting the events of the war. The Emperor Trajan appears in this account some seventy times.

The inscription, cut into a marble slab over the door at the foot of the column, measures 10 feet by approximately 4½ feet and originally contained 172 letters, 28 punctuation marks, and 3 numerical signs. These letters represent the finest examples of the greatest period of Roman monumental lettering. As such they have been the subject of study for many centuries and have appeared in countless books devoted to letterforms.

The most recent of these studies, and the most authoritative, was made by Rev. Edward M. Catich from 1935 to 1939. Father Catich made a series of rubbings from the inscription. He published them, along with a treatise on the letters themselves, in 1961. Prior to this most informative work, the principal source of information on the inscription has been the plaster cast in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Dependence upon this source has been necessary owing to the difficulties of working with the original, a scaffolding being required in order to make rubbings or even photographs. In terms of obtaining precise information on letter proportion, the Victoria and Albert Museum casting, which was in turn made, in 1864, from a French metal copy, suffers from the distortions and defects of multiple copying.

The letters of the cast have been painted to simulate the original practice of painting inscriptional lettering. This has also introduced errors, as in some instances the paint has extended beyond the edges of the letters and in others has been short of the outlines, thus exaggerating certain letter features. In addition, there is distortion in the photographs of this cast, a serious matter, as most of the modern studies of the Trajan inscription are based upon these photographs.

In many of the books which discuss the Trajan letters, the authors have pointed out that their reproductions are made “in the spirit” of the original and encompass their personal aesthetic preferences. This is of course permissible, but it was the opinion of Father Catich that what needed to be done was to produce same-size reproductions from rubbings and tracings. This he did, making available for the first time for everyone interested in beautiful roman letters, the most magnificent examples of their kind that are now known to exist.

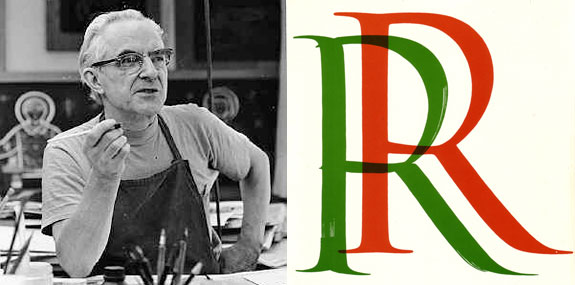

For many years Father Catich refrained from publishing his redrawn Trajan alphabet, but he decided to proceed with their publication when William A. Dwiggins enthusiastically recommended that he make them available to students of lettering. “Father Catich’s portfolio,” said Dwiggins, “will be a good tool in art schools—and elsewhere—for renovating standards that have become a trifle frayed in these revolutionary years.”