February 4

Probably the earliest known use of a printer’s mark which pictured the printer himself occurred in a book, Heures à l’Usaige de Rome, published on this day in Paris in 1489 by Jean du Pré. The device was apparently cut in relief on metal, a method quite common in French books of the period. This particular mark did not show any of the tools of the printing craft. That innovation came into use about twenty years later and has been of value in the attempts to trace the development of printing.

Probably the earliest known use of a printer’s mark which pictured the printer himself occurred in a book, Heures à l’Usaige de Rome, published on this day in Paris in 1489 by Jean du Pré. The device was apparently cut in relief on metal, a method quite common in French books of the period. This particular mark did not show any of the tools of the printing craft. That innovation came into use about twenty years later and has been of value in the attempts to trace the development of printing.

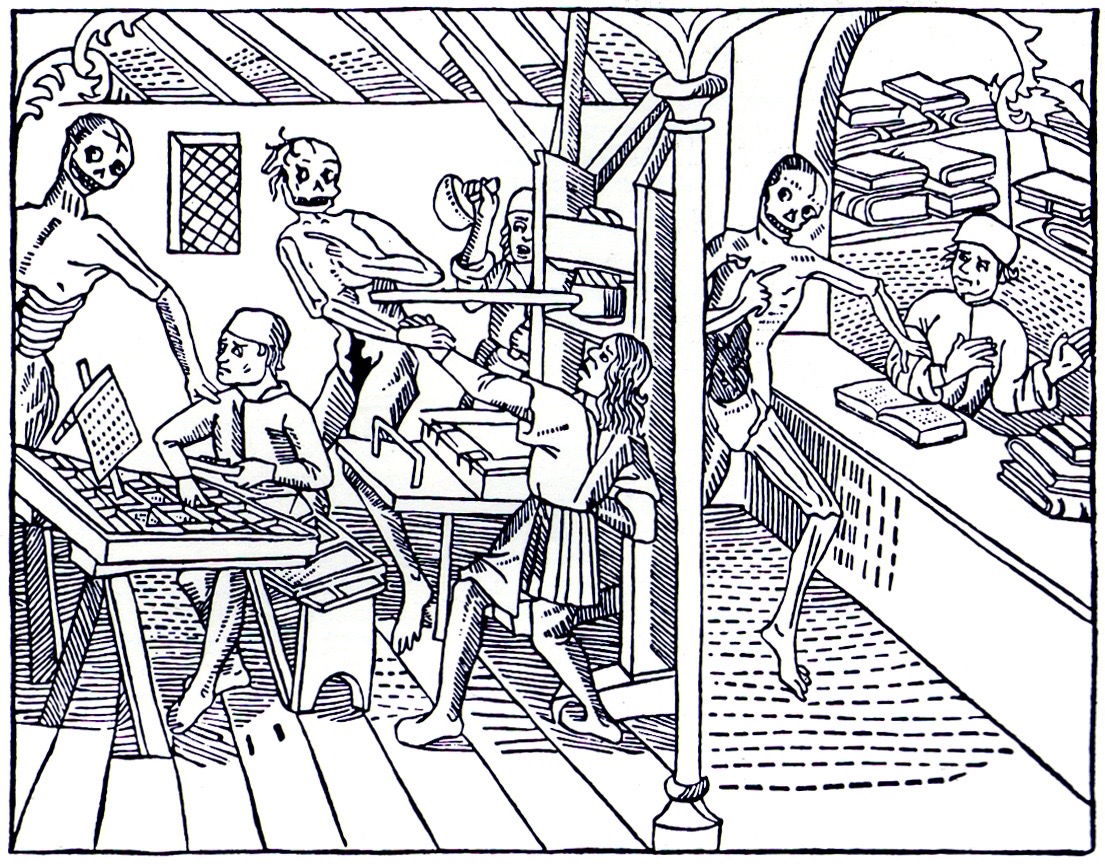

While the first printer’s trade mark depicting a printing press was used in 1507 by Jodocus Badius Ascensius of Lyons and Paris, the implements of the printing office were shown in a somber illustration in an edition of Danse Macabre, printed in Lyons in 1499. This wood cut vividly renders a scene in which death, represented by three skeletons, interferes with a seated compositor at his case. Two pressmen are shown at their machine, and another section shows a clerk in a bookshop.

The most notable of all printer’s devices is the crossed shields used by Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer in the magnificent Psalter of 1457. There have been a number of attempts to decipher the cryptic symbolism delineated in the shields. H.W. Davies, the authority on printer’s marks, believed them to be ancient German house marks, although admitting the possibility that they are merely printer’s rules. Most of the early marks—particularly those of northern European printers—are badly designed, being overly decorated and much too large for their purpose, which was merely to indicate the printer of the book in which they appeared. Notable exceptions to this trend were the marks of the great Venetians, Nicolas Jenson and Aldus Manutius.

Jenson’s device was from the hand of a partner, Johannes de Colonia, and is the beautifully simple orb and cross, printed in reverse. Variations of this mark have been so widely used that it undoubtedly represents the most commonly encountered of all press devices. As in the crossed shields of Fust and Schoeffer, there is some controversy concerning the origin of the orb and cross. It is probable that it derives from pagan origins, although the religious symbolism is most frequently mentioned as inspiration. In many instances its use may be attributed merely to imitation, from one printer to the next. The same device has survived into our own time in the beautiful setting of it designed by Frederic W. Goudy for his Village Press and outside of the industry, in the more prosaic trademark of the National Biscuit Company.

The Aldine press mark, first used in 1502, is the dolphin and anchor representing quickness (dolphin) and firmness (anchor). Aldus adopted the device from a medal of the Emperor Vespasian given to him by the humanist Pietro Bembo. Owing to the popularity of its originator, the dolphin and anchor quickly became the most widely pirated printer’s mark. Its modern counterpart is the trademark of the publishing firm of Doubleday.

A tip of the Typochapeau for his aiding & abetting us with this post’s imagery for to Paul Moxon, who has himself plenty to say about printers’ marks.