February 5

“The generosity of your invitation to me to speak on this important occasion leaves me a trifle bewildered. I am so accustomed to being told to keep my opinions to myself that being thus unexpectedly encouraged to express them gives me some cause to wonder if I have, or ever had, any opinions upon the graphic arts worth expressing. . . . So if I accept it as wholeheartedly as I believe it was given—if I take you at your word and say things that I have long wanted to hear somebody say—I hope it will not be thought an abuse of this kindly tendered privilege.”

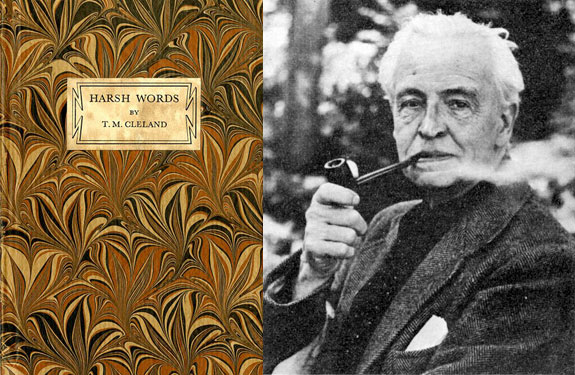

So began one of the most forthright statements ever made before an audience gathered to celebrate the opening of a Fifty Books of the Year Exhibition. The speaker was Thomas Maitland Cleland, one of America’s most distinguished typographers. The date was February 5, 1940. Cleland’s address, described by one listener as “refreshing as a cool, fresh breeze,” was thereafter entitled Harsh Words, and was so received by many of the younger designers who were present that evening.

T.M. Cleland had long since earned the right to either praise or damn the graphic art of his times. From 1900 he had been a first-rate book designer, advertising typographer, type designer, and artist. While he was perhaps most at home in the production of traditional typography, he had nevertheless been “contemporary” for most of his professional life. During the thirties many designers had not come to terms with any particular school. As a result much shoddy work was being produced that was merely imitative of a number of conflicting artistic creeds. It was this approach which prompted Cleland’s contempt when he said:

“Much as I am filled with admiration and respect for many individual talents and accomplishments that still contrive to exist, they seem to me to stand unhappily isolated in what I can’t help viewing as artistic bankruptcy and cultural chaos. . . . To paraphrase a remark in the concluding chapter of Updike’s classic work on printing types, it has taken printers and publishers five hundred years to find out how wretchedly books and other things can be made and still sell.

“. . . The idea that originality is essential to the successful practice of the graphic arts is more prevalent today than it ever was in the days when the graphic arts were practiced at their best. The current belief that everyone must now be an inventor is too often interpreted to mean that no one need any longer be a workman. Hand in hand with this pre-meditated individualism goes, more often than not, a curious irritation with standards of any kind. The conscious cultivator of his own individuality will go to extravagant lengths to escape the pains imposed by a standard. . . .

“It seems to me that all art was modern when it was made, and still is if it is suitable to life as we now live it; and I look in vain for any applied art worth the name that was not also, in some sense functional. From the buttresses of a gothic cathedral to the gayest Chippendale chair one finds, upon analysis, a perfect work of engineering perfectly adapted to its purpose. If this were not so, these things would hardly have endured for so long a time. . . . As students and beginners in search of truth, we are today being pushed and pulled about by no end of such bogus preachments—familiar faces with false whiskers—old and common principles dolled up with new names and often used to account for incompetence and laziness.”

Further Reading

Harsh Words from T.M. Cleland by Steven Heller