January 11

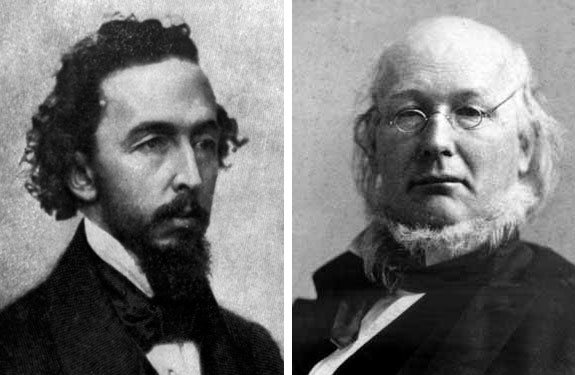

“I wish you would resolve henceforth to write one such article per week,” wrote publisher Horace Greeley to Bayard Taylor, born this day in 1825,” and sign your own initials or some distinctive mark at the bottom. I want everyone connected with the Tribune to become known to the public (in some unobtrusive way) as doing what he does, so that in case of my death or incapacity it may not be feared that the paper is to die or essentially suffer.”

Bayard Taylor, born on a Pennsylvania farm, was another of those 19th century printer—such as Mark Twain and William Dean Howells—who distinguished themselves in the world of literature, although his fame had none of the enduring character of these printer-writers. Today, Taylor’s poetry and novels are considered to be quite inferior, even though they were widely praised during his lifetime.

Taylor’s great love for books and literature led him at the age of seventeen to become a teacher. However, he quickly found that such a profession was not to his liking and instead apprenticed himself in the office of a weekly newspaper in West Chester, Pa. During his apprenticeship he became infatuated with the idea of becoming a poet, publishing a book of verse when he was nineteen and in addition contributing to various periodicals. Following his four years of indenture Taylor decided to go to Europe. To help finance his venture, he contracted to write letters about his travels to newspapers and magazines. With one hundred and forty dollars, of which twenty-four was spent for passage on a sailing vessel, the youth left his home and spent two years in Europe, traveling mostly by foot, and writing of his experiences. Upon his return he published Views Afoot, or Europe Seen With Knapsack and Staff, which was an immediate best seller, establishing his reputation.

Taylor next attempted to publish a weekly newspaper. He found the experience tame indeed, as he was now corresponding with Longfellow and Emerson, and receiving many requests to lecture about his travels. Horace Greeley, publisher of the New York Tribune, hired him as a correspondent, and Taylor very quickly became that paper’s crack travel reporter, entertaining the nation from a variety of exotic places.

In 1862–63 he was Secretary of Legation in St. Petersburg, Russia, and following the Civil War he continued his travels. In 1876 Taylor was selected to write the National Ode on the occasion of the Centennial Exposition. In 1871 he published his most important work, a translation of Faust. On the strength of this widely admired translation (which modern scholarship now considers to be second-rate verse) he was appointed Minister to Germany, in which office he died, shortly after arriving in Berlin in 1878.