January 22

In a bull dated January 22,1587, Pope Sixtus V issued a mandate officially recognizing the press which he had ordered established the previous year in the Vatican Library. Called at first the Typographia Vaticana, this press has survived under a variety of names and is presently known as the Vatican Printing Office.

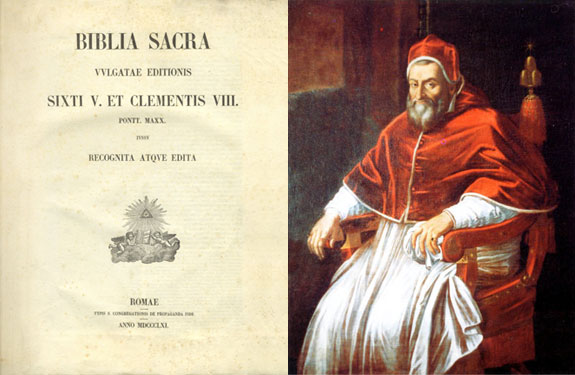

Sixtus V, the Pope of Catholic Reform and considered to be one of the greatest statesmen to occupy the Chair of St. Peter, had originally decreed the press to be set up in order to print a Vulgate Bible. He brought from Venice a printer named Dominicus Basa to take charge of the production of this work, which was finally completed as a three-volume folio in 1590, the year during which Sixtus died. The title of this work was Biblia sacra vulgate editions, tribus tomis distincta jussu Six. V. pontificus maximi edita; Romae, ex typographia apostolia vaticana. In a further bull affixed to the first volume of this edition, Sixtus V warned of excommunication for all printers, editors, etc. “who in reprinting this work shall make any alterations in the text.”

No corrector of the press was His Holiness, however. In spite of the fact that he personally examined every sheet as it was pulled from the press, this Vulgate was, as described by one source, “without a rival, to the amazement of the world—swarming with errata.” To the great joy of 16th century heretics, the erroneous words were covered over with pasted corrections, and papal infallibility in the art of proofreading became a thing of the past.

Gregory XIV, successor to Sixtus V, ordered the Vulgate suppressed. Clement VIII, who succeeded Gregory, decreed that it be revised, and having made alterations in the text thus ran the risk of excommunication. The corrected edition became the official text of the Vulgate as prescribed by the Council of Trent.

Aldus Manutius the younger was appointed to the directorship of the Typographia Vaticana in 1590. Grandson of the celebrated Aldus, he had published his first work at the age of eleven. He was a professor of eloquence at several universities, attesting to his greater interest in literature than in printing, although he had inherited the great printing office which had begun in Venice a century before.