A Few Reflections On a Man Named Alfred A. Knopf

In a recent issue of New York Times Book Review, a writer was questioning the emergence of conglomerate ownership in the formerly preponderantly individualized book publishing business. Discussing this problem with an executive of one of the conglomerates (for example, Time Inc. owns the old Boston house—Little, Brown—and RCA owns Random House, Knopf, etc.) this man stated that there were many advantages to large corporate identity. He cited as a tyrant Alfred A. Knopf, who first entered the industry some 60 years ago and earned an enviable reputation for integrity as a publisher.

In a recent issue of New York Times Book Review, a writer was questioning the emergence of conglomerate ownership in the formerly preponderantly individualized book publishing business. Discussing this problem with an executive of one of the conglomerates (for example, Time Inc. owns the old Boston house—Little, Brown—and RCA owns Random House, Knopf, etc.) this man stated that there were many advantages to large corporate identity. He cited as a tyrant Alfred A. Knopf, who first entered the industry some 60 years ago and earned an enviable reputation for integrity as a publisher.

“There’s no Alfred Knopf in the big companies insisting that he wants all book jackets to be yellow,” said this fellow. “At Knopf nobody but Mr. Knopf could do anything for 40 years.”

This is a little like saying that nobody but Bruce Rogers could produce allusive typography, or that nobody but Bill Dwiggins could turn out those unique decorative patterns.

Let’s turn to Mr. Knopf for a few moments, since he exemplifies the individual approach, not only to first-rate book publishing, but to what is more vital to typographers and designers, absolutely first-rate book production—design, format, and indeed the whole package represented by a printed book. And probably most important, the Knopf books were competitive with those turned out by publishers who didn’t know a colophon from a headband.

In this matter of the blandness of the conglomerate compared with the judgment of the individual, it’s pretty easy to separate the two cultures, particularly when that individual is Alfred A. Knopf.

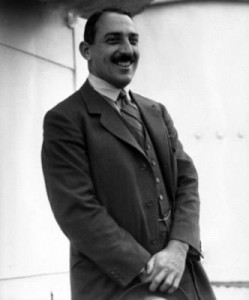

Lord Alfred, as he was called by some of the vassals who toiled in his publishing office, undoubtedly was a rather unique personality, and I refer not only to his sartorial splendor, which was monumental, but to his old-fashioned sense of responsibility as a publisher.

Virtually alone of all his fellows along Publisher’s Row, he knew his designers, admired them, and singled out a few of them for particular mention in his books, in jacket copy, and even in his advertising. Those fortunate designers, such as W.A. Dwiggins, who produced some 500 Knopf titles between 1926 and 1955, Warren Chappell, George Salter, Rudolph Ruzicka, and Herbert Bayer all were given great freedom in their designs. Their books, along with those turned out by the in-house designers at Knopf, represent a most distinguished contribution to American trade book manufacturing. It is not likely that we will ever again see their like in normal book publishing, except for occasional titles.

Another of Knopf’s idiosyncrasies was to include in every volume he published, a “Note on the Type,” which was a short treatise on the design of the type selected for the book. While colophons have been used since 1457, when the “Psalter” of Fust and Schoeffer was printed in Mainz, they are not commonly seen except in private press or limited edition printing.

The appearance of a colophon in a Knopf volume indicated a civilized awareness on the part of its publisher that the reader was intelligent enough to be interested in the physical appearance of the book he was reading, as well as in the subject matter. There is no question that many of the purchasers of Knopf books became aware, for the first time, that printing types had meanings of their own. And from this awareness came a more educated and sympathetic understanding of the typography of all books.

But did this esoteric activity upon the part of one publisher sell books? This presumably is the point made by those publishing firms which cared not a dot whether or not their books confined widows or ill-fitted initials. It’s pretty easy to deride those purists who place undue emphasis on the typographic treatment of a piece of printing and by so doing forget its reason for being. But to err in this manner is at least closer to sitting with the gods.

For a number of years book production has been plagued by economic difficulties. Publishers, faced with increasing competition from other media, have turned to new methods of production which will make them more competitive. High-speed photo-typesetting procedures have been one way of increasing production and thus lowering unit costs, but unfortunately this has further reduced the individualized approach to bookmaking sought by some publishers in the past.

There appears to be little likelihood therefore, that publishers such as Alfred A. Knopf will he allowed their “tyrant” whims in the future. Possibly the main animating principle in present technological change is that faster and cheaper are synonymous with better. We’ll know a little more about such rationalizations when most books are produced on cathode ray tubes with equipment designed for computerized page make-up.

It is doubtful whether esthetic capabilities will be properly nurtured by such mechanization of input, and no matter how feasible such an operation may be, the intimate and individualized approach will necessarily be tailored out of the program. Not, of course, because the equipment is not capable of such refinement, but primarily because the person now turned on by the challenge of producing distinctive books will be off doing some thing else and will never be enticed into even coming near a publisher’s office.

So Alfred Knopf is or was a tyrant. In his eighties now, he’s not as active in his publishing career (he established his own firm in 1915), and obviously he’s slowing down. Even widows turn up in Knopf titles these days, but he knew what he wanted in bookmaking. . The proof of this can be obtained simply by looking at any of the thousands of books which bear his imprint. Such individuality can’t be all that bad for the typography of our times.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the November 1973 issue of Printing Impressions.

B – R – A – V – O