Anatomy of a Type–3: Caslon, Part 1

One of the most widely known types of existence is that which bears the name of its designer, William Caslon, and English engraver who cut it about 1720. It is an indisputable fact that the type has been overpraised, particularly in this century, by most of the outstanding typographers. Beatrice Warde, in her essay on the choice of typefaces, mentions the “almost superstitious regard for Caslon Old Face” that has existed in our time.

Contemporary typographers, who have a variety of riches at their disposal, as evidenced by the bulging pages of the current specimen books, are not to be blamed for their disenchantment with Caslon and the period it seems to represent.

But their disapproval runs counter to the opinion of their more traditionally oriented brethren who point to the statement of Daniel Berkeley Updike, that most distinguished of American printers, who wrote in his Printing Types: “In the class of types which appear to be beyond criticism from the point of view of beauty and utility, the original Caslon type stands first.”

Buoyed by such remarks, the typographers who grew to maturity prior to 1930 learn to love Caslon, and more importantly, acquired efficiency in its use. For most of his formative years Bruce Rogers used Caslon in book after book, while Carl Purington Rollins, the great Printer to Yale University, acquired an international reputation with the type. Even on Madison Avenue, the New York typographer Hal Marchbanks was known as a “Caslon printer,” being responsible for its use in a large volume of commercial and advertising printing.

The result of all this activity by printers received their initial inspiration from the English private press movement as represented by the Kelmcott, Doves, and Ashendene presses, was to place Caslon in its present ambivalent position. The contemporary typographer may very will ignore the design, but it sometime he is bound to feel uncomfortable about his rejection of it.

Certainly Caslon is far from being forgotten. It turns up regularly in national advertising. For example, the current issue of Esquire contains seven full-page ads in which it is used for display. All of the manufacturers of phototypesetting equipment have transferred the type to their film grids for both text and display typography. And American Type Founders just last year brought out another version, Caslon 641, even though in the vault of the company rest the matrices for some three dozen variations of the design.

The interest in Caslon types began early in the 18th century. A group of London printers and booksellers prevailed upon a young engraver named William Caslon to cut for them a font of Arabic type for a series of religious tracts then being planned for the press, by means of which it was hoped that people of the Near East would be induced to take up Christian principles.

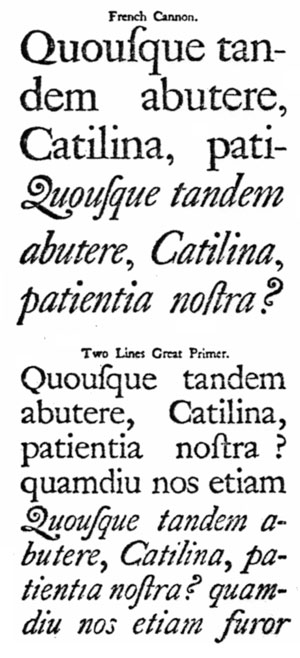

This is a sample of two sizes taken from a reproduction of Caslon's first specimen sheet, issued in 1734. The actual specimens were about twice the size shown.

According to one account, Caslon, when he had finished the task and was ready for proof, that is name in Pica Roman (12-point) in order to identify the proof. It was these few letters which attracted the interest of his sponsors in which resulted in Caslon’s devoting all of his energies to the cutting of types.

At that period there was little typefounding being done in England, and for a long time printers had depended upon Dutch sources for their type. During the 17th century the restrictions of the Star Chamber had served to eliminate competition in the field, but by Caslon’s time these had been removed, creating a climate which was just right for a new typefounding venture.

The preponderance of Dutch types in English printing offices, however, made it inevitable that Caslon would be influenced by their characteristics. Even though his types have been praised as the personification of English style, they were basically copies of the earlier Dutch forms, although much better fitted and better cast.

It was not until 1734 that Caslon issued his first specimen sheet, a broadside which has been widely reproduced in printing histories and is thus well-known to all students of typography. It is into the roman and italic types, this sheet showed a number of exotics such as Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, etc.

Caslon’s success as England’s most competent punchcutter undoubtedly contributed to the lack of appreciation by printers of his period for the typographic developments then taking place on the Continent. During most of the 17th century, the Dutch types had dominated European printing, but in the last years of the century there were some interesting experiments taking place which were to have long-ranging affects upon the design of printer’s types.

Philippe Grandjean, the French punchcutter, had created the famous roman du roi, a revolutionary type which eventually led the way to the style now called modern. Pierre Fournier, a contemporary of Caslon, was profoundly influenced by these types introduced several variations of them.

None of this activity had any effect upon English typefounding, so that Caslon’s very excellence in his craft actually deterred further experimentation with new forms.

William Caslon died in 1766, but his foundry remained in the family. The last of the Caslons, Henry William, died in 1874, following which the name was retained through subsequent changes of ownership. Finally it was acquired by Stephenson, Blake & Company, which now appends to its name, the Caslon Letter Foundry.

In the middle 18th century, the types of John Baskerville brought about the changes which resulted in the eventual decline of the earlier interest in the Caslon types. The styles of Didot in France and Bodoni in Italy were radically affecting European typography, with the result that the oldstyle types were soon completely out of favor. In the 1805 specimen book of the Caslon foundry, not a single oldstyle was shown.

It was not until 1844 that Charles Whittingham produced at the Chiswick Press the book, The Diary of Lady Willoughby, which was set in Caslon and which is credited with returning the type to popular favor, regaining the esteemed it had earlier enjoyed. By 1900 it was once more a standard and was soon to be elevated to the unique position which prompted the aforementioned Updike panegyric.

Next month I will examine the various styles of Caslon presently available.

’This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the September 1967 issue of Printing Impressions.