Charles Broad—“Mr. Antique”

When Charles “Mr. Antique” Broad publishes his life story, it’s going to be set in 12-point Century Schoolbook! At least that’s the present plan of the man who claims to have the largest and finest collection of antique type face matrices in the world.

Charles Broad has been a Monotype machinist operator and type founder for 47 years, a printer since 1912. He wound up on the Monotype instead of Linotype when back in 1916 he found that the Lino class in the Harlem Evening Trade School was booked up six months in advance.

Mr. Broad was one of the early “tramp printers,” but different in one respect—his wife and four growing children tramped with him! He joined the printing department of the Chicago Post Office in 1938 and stayed there until his retirement in 1957. But Mr. Broad just didn’t “have enough sense to sit down and loaf like other retirees.”

Mrs. Broad didn’t fully realize what she was saying in 1957 when her husband retired, “You’ve got so much stuff in the garage, you haven’t got room for the car. Why not take it all to Phoenix and go into the typesetting foundry business?”

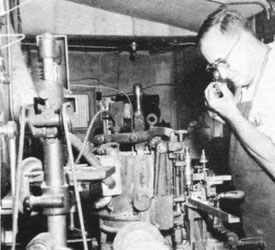

So he did, and earned his nickname “Mr. Antique.” He made a study of antique type faces and antiques in general, and then began making “new” antique type faces using 19th-century faces as patterns. Currently, he uses reproduction proofs, blow-ups, retouching, and then engraves the matrices.

This is a sample of Mr. Antique's typography; it's also representative of the philosophy he presents in his monthly "Dingbat Gossip."

Right now Mr. Antique handles his shop by himself—everything from typefounding to office work to janitor work. Years of income tax, unemployment tax, etc., have him tired of the red tape necessary to hire help, and then, as he says, he gets only federal “womb to tomb” goofs.

Mr. Broad says you can’t find instructions for running a foundry in a book. He calls experience the art of “not making the same mistake too many times—make some new ones.”

Mrs. Broad is gone now, but Mr. Antique occupies himself with his four granddaughters, his shop, and publishing his monthly “Dingbat Gossip,” a little bulletin in which he expresses his views on philosophy, the current state of affairs, and other signs of the times.

This article first appeared in the November 1962 issue of The Inland Printer/American Lithographer. Although uncredited, it is most likely written by Alexander S. Lawson.