Decorative Letters of Past Century Inspire Revival

- Hey-day of decorative letter is not yet over; still used as “modern” style

- Trends of the nineteenth century brought out in twentieth century printing

- European typefoundries lead U.S. in the production of display faces

The nineteenth century has had the questionable reputation of being a period of low standards and printing. But the logical advances of the industrial revolution brought about attempts to raise production and lower hour costs but resulted in the detriment of style.

However, the wildly expanding economy did result in a great deal of experimenting with the shape of the roman letter. These changes are apparent in old specimen books, which listed page after page of display types in kaleidoscopic array. The demands of the nineteenth century marketplace called, apparently, for novelty above all else in the production of commercial printing.

“Fresh” Approach of Old Types

Is frequently the fashion today to decry the typographical style prevalent one hundred years ago. But the contemporary designer on the outlook for the “fresh” approach is increasingly aware of many of the old types and is adapting them to current needs. Of course type revivals are constantly recurring and will continue until someone invents a new alphabet.

Probably the most familiar revival is that of the type now called Ultra Bodoni, which occurred during the Twenties. While it is obvious that this type does have some resemblance to the contrasts of Bodoni, it can scarcely be credited to the account of the Italian letter founder.

Nevertheless, this type, issued under several similar names, has been almost a standard item of manufacture by all foundries and machine companies. More recently, the wide gothic and extended square serifs have come again into wide use. It would appear that both advertising designers and typefoundries have been taking a closer look at the display letters of the past century.

Just a few years ago, the only people interested in old types were the “collectors,” who expressed their nostalgia in lectures at “old timers nights.” Modern typographers were content to let collectors argue about whether or not they had obtained a font of Bijou or Bizarre, and paid attention only when they wanted a line of Buffalo Bill for an ad.

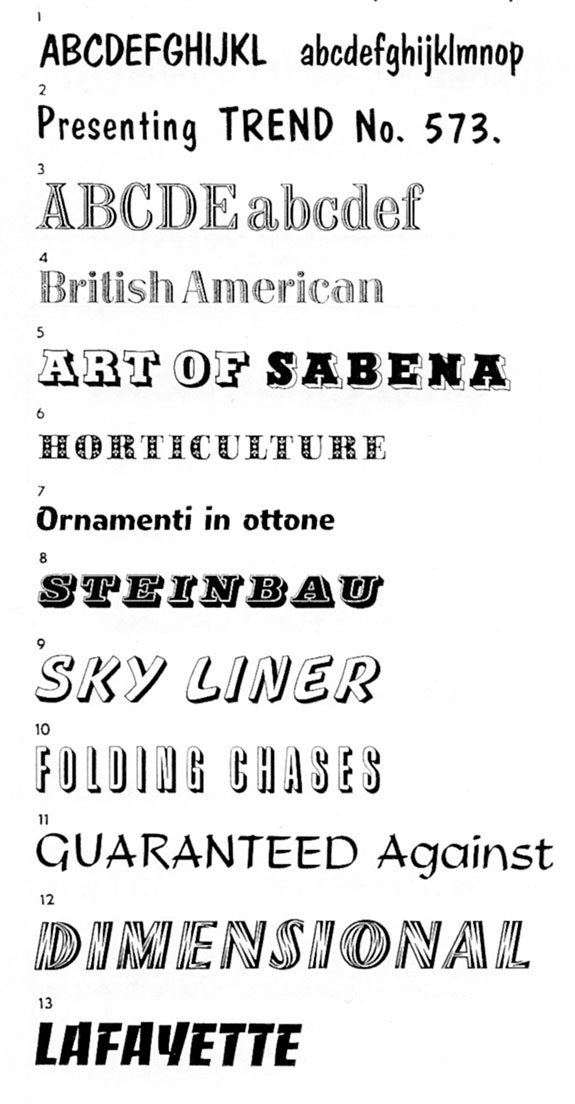

Here are samples of 1 Dom Casual, 2 Trend, 3 Chisel, 4 Ornata, 5 Duo, 6 Saphir, 7 Ritmo, 8 Profil, 9 Riccardo, 10 Graphique, 11 Studio, 12 Flash, and 13 Banco for a comparison of styles.

The interesting decorative types has never really lapsed. Now and then every typefounder has produced a type designed to meet display requirements only. During the postwar period a number of new faces in this category have been designed.

Increasing use of photolettering has made unnecessary and uneconomical, in the opinion of some foundries, the casting of new display types, but the demand is constant from the commercial printer who prefers to have his display types in hard metal rather than on film.

Several of the current crop of decorative letters are revivals, produced without change from nineteenth-century originals. A good many, however, are the result of current ideas of what printing should look like, and care must be exercised in their use to obtain the best effect. Too often, the use of revivals is limited to a period style. While this is permissible in some jobs, it does nothing to justify the use of a revival type in mid-twentieth-century work.

It must be acknowledged that most of the new decorative faces are the product of the European countries, which are now competing strongly for the American dollar. In spite of the setback of World War II, the Europeans have done an amazing job. Most of the foundries which are either destroyed or completely incapacitated during the hostilities are now back in business, with most of their formerly successful types, and many new designs.

In addition to German foundries, which in the Twenties and Thirties were actively producing type for American printers, we now see Swiss, French, and Italian organizations making overtures toward this country. Of particular interest are the excellent type specimen sheets calculated to show off the new designs to the best vantage. Due to higher production, American manufacturers restrict themselves almost exclusively to the more utilitarian showings of new types. In this respect they offer little competition.

U.S. Offers Few New Display Faces

In the United States, the most successful postwar display type has been Dom Casual, design for ATF by Peter Dombrezian in 1950. This follows a popular hand lettering style of irregularly shaped letters of casual stroke. It is also available in an italic form, Dom Diagonal, and in a boldface version.

Somewhat similar to Dom Casual is a recent type called Trend, produced by Baltimore typefoundry.

The famous English concern, Stephenson, Blake, and Company, of Sheffield, experimented in 1939 with a shaded version of Latin Bold Condensed. This effort resulted in Chisel, one of the best-known of the European importations. Not until after the war did production get fully underway, but already the type is well-established in the United States.

The Klingspor foundry of Frankfurt, Germany, whose types are familiar in America, has offered to new items in the decorative category—Ornata, a delicate letter with inlaid herring-bone pattern and a star; and Duo, a versatile face, almost square serif, which is available as a three-dimensional letter, and outline, and a two-color shaded letter.

The Stempel Foundry, also located in Frankfurt, is fortunate in having on its staff one of the world’s most talented type designers, Hermann Zapf. In 1953 he cut the type Saphir, a capital letter which contains a floral pattern in reverse, and which is formed with the same skill evident in Zapf’s roman types, those called Palatino and Michelangelo.

During the last few years American printers have been quite enthusiastic about the types of the Nebiolo foundry of Turin, Italy, where many colorful and interesting specimen showings have been produced. And evenly drawn, slightly sloped capital letter called Ritmo is the Nebiolo contribution to recent display types.

Switzerland Offers Profil

From the Haas’che foundry in Muenchenstein, Switzerland, has come a variety of postwar designs, marketed in this country by the Amsterdam organization. Profil, a three-dimensional capital letter, slightly sloped and of square serif characteristics is the best known. It is already used a great deal by American typographers. Two other “3-D” faces are Riccardo, and open cap type, freely drawn in the “cartoon” pattern; and Graphique, a condensed sans serif, also available in caps only.

Typefoundry Amsterdam has been successful with Studio. Drawn in 1950, it is one of the best of the cartoon-style types. Their most recent innovation is a series of initials called Raffia, styled in a Baroque pen-flourish manner.

Flash, a type design by one of France’s leading type designers, Crous-Vidal, has been cut by the Fonderie Typographique Francaise in Paris. This is a slope opened capital with lightning flashes drawn into the stroke. When used in this country it will probably be given a surname so that it will not be confused with the well-known Monotype face.

Another French company, the Fonderie Olive, has produced Banco, a type similar to the Italian face, Ritmo, mentioned above, the more condensed and available in caps only.

It appears that the hay-day of the decorative letter is not yet over. We moderns will have something to offer the printers of the next century, or looking for a unique approach to typographical design.

This article first appeared in “The Composing Room” column of the August 1956 issue of The Inland Printer.