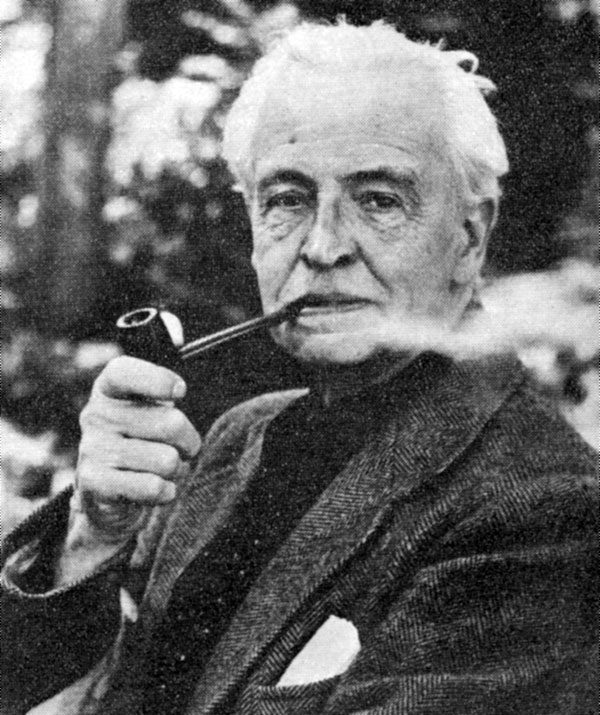

T.M. Cleland: Outstanding American Typographer

The last of that triumvirate of creative American typographers who were born in 1880, and about whom I have been writing in this department, is Thomas Maitland Cleland—a man whose personality was completely at variance with that of either Carl Rollins or W.A. Dwiggins. Whereas Rollins brought to his work an almost evangelical persuasion, and Dwiggins a philosophical whimsy, Cleland tended to express himself with forthright candor and was not at all backward about differing with the conventional wisdom of his era.

All three however, were representative of what Joseph Blumenthal recently termed “a highly creative period in the history of the printed book.” Blumenthal, the most distinguished of living American printers and whose own career overlapped that of the three whose centenary we are celebrating, has writing that along with Goudy, Bradley, Ruzicka and Nash they “earned the right to be called a heroic generation.”

Naturally enough, most great printers who came on the scene after Benjamin Franklin were practically unknown outside of the craft in which they labored. I was reminded of this recently when an item in the press referred to the honoring of W.C. Fields on his centenary with a commemorative postage stamp.

As far as I know, the only printer ever to appear on a stamp besides Franklin was Warren G. Harding, who reached that peak of eminence by his short occupation of the White House. The fact that he could lock up a form was forgotten, once he decided to trade in his comp stick and seek political fame. In 1964 an effort was made to get Fred Goudy on a postage stamp for his 1964 centenary but not even the Public Printer had sufficient clout to influence the Post Office Department. It was thus unlikely that a mere typographer will ever make the grade.

T.M. Cleland (he preferred the initials rather than his full name) was a doctor’s son, born in Brooklyn, N.Y., and brought up across the river in Manhattan. We know very little about his early life, but it must have been reasonably affluent. However, by the age of 15, he prevailed upon his father to allow him to drop out of school and enroll in what was then a down-at-the-heels art school called the Artist Artisan Institute. Not at all a good student, Cleland remained but a few months.

However, while there, by sheer accident he happened to observe a fellow student at work upon an ornamental drawing. Upon enquiring, he was told of the method of reproduction by which such a drawing became a printing plate.

Apparently intrigued by this information, he immediately went home and began work on a set of ornamental initial letters. This ld to a trial submission of his project to John Clyde Oswald, then editor of the American Bookmaker, who thought enough of it to publish it in the periodical. Cleland was so pleased by his first appearance in print that he decided to pursue further what looked like a most exciting career prospect.

It was the circumstance of this early recognition of an inherent skill which set Cleland’s direction toward ornamental design, a field in which he became pre-eminent among American graphic artists. His first commission came a short time later—an ornamental border for the cover of a small sports magazine. While it took him almost three weeks to produce this border—drawing and re-drawing—the five dollars which he received in payment convinced him that he was now a professional, at the age of 16. Whereupon he left the art school and purchased a cop of Walter Crane’s The Decorative Illustration of Books, then on display in Macmillan’s Fifth Avenue book shop. A whole new world was opened up to him in the pages of this fine book. He became acquainted with the work of contemporary designers, such as William Morris and Aubrey Beardsley, and most important, the American ornamentalist and practical printer, Will Bradley.

Cleland now became involved in the work of a small print shop through a piece of work which he brought to it. He very quickly took to typesetting and the operation of a platen press. It wasn’t long before he was thoroughly familiar with all the activities of the printing plant—owned fortunately, by a friend of his family. With youthful enthusiasm he sought out work which he could personally produce. He was soon allowed access to the shop at night, and in this way became fully involved in every step of production.

The next connection he made was as designer for a short-lived shop called the Caslon Press, owned by Frederic T. Singleton, a disciple of Will Bradley. Upon its demise he acquired his own treadle press along with a few fonts of type and set up for himself in the cellar of his home. With such limited facilities, he did not produce anything of importance, but one small book did attract attention as far away as Boston. He was induced to move to that city to set up what was called The Cornhill Press. However, the sponsors never did provide the funds which has been promised, and as a result he attempted to continue on his own, a dubious decision considering his relative inexperience.

Cornhill Press lasted but a year, but one important outcome of his stay in Boston was meeting Daniel B. Updike, who took an interest in his work and commissioned small jobs from him. Updike attracted by the dedication which Cleland brought to his designs, gave valuable aid by providing constructive criticism of the young man’s efforts.

Although Cleland found it necessary to return to New York, Updike continued to supply commissions for work at the Merrymount Press and remained his firm friend until his own death in 1941. In fact, the Boston printer mentioned Cleland in his great book, Printing Types (1922). In his discussion of Bodoni type he wrote: “it can be utilized for short addresses, circulars and advertising; with great success—as in the charming use of it by Mr. T.M. Cleland. To printer-designers as skilful as Cleland it may be recommended.”

Updike, of course, did not mention in his book the typefaces which Cleland designed upon his return to New York. And Cleland would have been the first to admit that it did not belong in Updike’s pages. The type was drawn at the request of the Bruce Type Foundry, then in its last days. Called Della Robbia, it was cut in 1903 and made its first appearance under the aegis of American Type Founders Co., which had purchased the Bruce firm in 1900. The type was extremely successful, and as recently as 1977 it was revived for phototypesetting. But it never aroused in Cleland anything but distress when in later years he was asked about it.

The only positive effect on the life of the artist of his one and only attempt to design a printing type was that the royalties from its production financed his first trip to Italy, where he became more fully involved in the study of Renaissance ornamentation, in addition to painting and sculpture. The result of such exposure was a firming of his resolve to continue as a graphic designer and to remain in the studio rather than to make further attempts to be a practical printer. Marriage and a second voyage to Italy the following year brought him to the maturity which was to result in his attainment of a position of first rank in American typographic design.

Cleland spent the next few years in freelance design, producing a variety of printed pieces and bindings and even venturing into the painting of an altarpiece for a church in Glens Falls N.Y. In 1907 he accepted an offer to become art editor of McClure’s Magazine. This gave him the opportunity to embark upon a consistent daily effort, very soon resulting in numerous designing innovations which revitalized the pages of that periodical to a point far beyond that of its competition. Although he remained with the magazine only two years, he acquired a reputation for his insistence upon the highest levels of craftsmanship.

A great contemporary of Cleland was Bruce Rogers, at this period establishing himself with the work at the Riverside Press in Cambridge. Whereas Rogers specialize in the art of the book, Cleland brought to commercial printing the same high standards of accomplishment. It was not until the last half of his life that Cleland ventured into book design, first as an illustrator, and then as designer-illustrator.

Next month I will complete this short account of the life of an outstanding American printer.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the August 1980 issue of Printing Impressions.