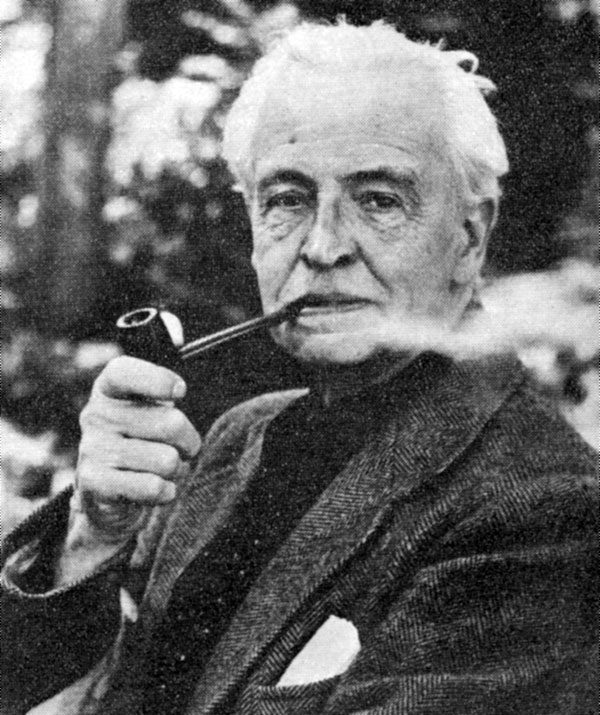

T.M. Cleland: Outstanding American Typographer—II

About 1915 Cleland was commissioned to design all of the publicity material for the Locomobile Co., then producer of one of the country’s finest automobiles. Realizing the breadth of this assignment, the designer once again returned to practical printing, setting up a complete shop in which he could design and supervise every step of production.

His first catalog for Locomobile was bound in boards. Set in Bodoni type with all of the illustrations and decorations being done by the artist, this catalog is a remarkable piece of work. To modern eyes it is of course a stylized antique, but it represents the most advanced thinking of its period in the production of sophisticated advertising.

Certainly no sales piece for an American automobile had ever received such meticulous attention and collectors of automobile advertising rightly prize this catalog. It has probably been surpassed on by the 1927 Cadillac catalog, another Cleland creation, which to the mind of this writer is the greatest piece of printed advertising to appear in the decade of the Roaring Twenties.

During the First World War the designer was in service. Upon his return he took almost a year to regain the position he had earned prior to his departure. The Strathmore Paper Co. asked him to produce The Grammar of Color, a project which engaged his attention as writer, designer, illustrator, and printer. Upon its completion he once again had to come to a decision whether to continue as a printer in addition to being a designer. The artist in him prompted his return to the studio and he was never again to be burdened with the practical matters of running a plant plus settings its artistic direction.

It was during the decade following the war that he became more involved with painting and illustration than with design. Fortunately, ATF had already persuaded him to design a number of typographic ornaments that were shown in combination with the cutting of Garamond in which the artist had collaborated as consultant to Morris Fuller Benton, the type designer.

Their availability as dingbats allowed numerous ordinary printers to enliven their productions with French 18th century ornamentation even when such decoration was unfit for its subject. But by the 1930s decorative printing had given way to the influx of Bauhaus design, particularly in commercial printing.

Traditional ornamentation survived for a number of years in the filed of book publishing, but even here the economic restrictions of assembling typographic decorations contributed to their decline. Today the private press printers have the filed to themselves. If decorative printing survives at all, it will be due to their efforts.

A major design job came in 1929 when Henry Luce selected Cleland to design Fortune magazine and to be its art director. This was followed by the design of Newsweek and a number of other periodicals.

Cleland was particularly proud of the opportunity to get into newspaper typography when the New York daily, PM, was introduced in 1940. The paper received the Ayer Newspaper Design Award as the outstanding tabloid in the United States, bearing out its designer’s objectives of restoring “order to what is now a typographic turmoil, piling emphasis until nothing can be seen or read.”

In 1932 Cleland had been enticed into book illustration by George Macy of the Limited Editions Club. Such was the artist’s addiction to perfection that the drawings for Tristram Shandy took over three ears to complete, thus delaying the publication of the book far beyond Macy’s original production schedule. Obviously Cleland could never have been properly compensated for this work, except by the rewards of posterity. But from that time he became more involved in book design.

The Overbrook Press edition of "Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut" designed & illustrated b T.M. Cleland

His masterwork as a designer and illustrator of books appeared very late in his career when Frank Altschul, proprietor of the Overbrook Press at Stamford, Connecticut. asked him to design and illustrate a new edition of Manon Lescaut.

At the age of 71 Cleland undertook this enormous task that took six years to complete. This was an edition limited to 200 copies, to be published at $250. The artist immediately decided that there would be no reproduced illustration in the book and that every picture would be an original print, “conceived, executed, and printed by the artist himself.”

The statistics of production are awesome. Utilizing new techniques in the art of serigraphy (silkscreen) Cleland supplied prints for 30 of the book’s 200 pages. This meant that he had to produce 6000 perfect picture pages for the entire edition. As each print averaged six colors, Cleland therefore had to turn out 36,000 individual impressions.

He furthermore decided to perform the entire task himself. Since his standards of production were of the highest, the odds were stacked against any simplification, with the result that he undoubtedly destroyed more prints than he saved.

One of T.M. Cleland's illustrations for the Overbrook Press edition of "Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut"

Cleland found it necessary to construct his own equipment for the transfer of his original drawings—made on non-shrink, non-swell plastic—to the silkscreen stencil. The type was printed by letterpress and the sheets delivered to Cleland for the printing of the illustrations. The Overbrook Press Manon is Cleland’s last statement as a typographer. During its production he suffered a stroke from which he never fully recovered. His final years, unfortunately, didn’t appear to be a happy period for him. No doubt he felt that time had passed him by and that he had been completely forgotten in his chosen field. He died at his home in Danbury, Connecticut on November 9, 1964.

It was in 1940 that he was honored with the gold medal of the American Institute of Graphic Arts, and in the same year he delivered his most famous statement on the typography of his time, one that was both warmly praised and widely castigated by his contemporaries and that contributed to his reputation as a curmudgeon during his declining ears.

Invited to present his remarks at the opening of the 1940 Fifty Books of the Year Exhibition, Cleland obliged with a polemic which has been honored with several reprintings under the title of Harsh Words. and harsh they were, since they were spoken in all sincerity by a consummate typographic craftsman who never gave anything but his absolute best to every job he ever undertook.

At the end of his talk, in which he found much to criticize in the sate of typography as he found it, around 1940, he quoted the Spanish philosopher, Ortega y Gasset, who had written, “To think at all is to exaggerate.”

He then remarked: “A careful measurement of anatomical detail in the drawings and sculptures of Michelangelo will reveal startling exaggerations of fact, but these enlargements of fact are but his medium for truthful expression. He gives us the figure of a man or woman more essentially true than could be made by any anatomist with micrometer calipers. So, I humbly pray, ladies and gentlemen, that you will apply no instruments of precision to my words—they are the best I cold find in this emergency for saying what I believe to be true. If you think me guilty of exaggeration, the foregoing remarks are my only defense. But if you accuse me of being facetious, I will tell you that I have never been more serious in my life.”

Harsh Words, stands therefore as a statement of belief in his own art by one of the finest typographers ever to follow his profession in the United States. It still deserves a hearing.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the September 1980 issue of Printing Impressions.