February 10

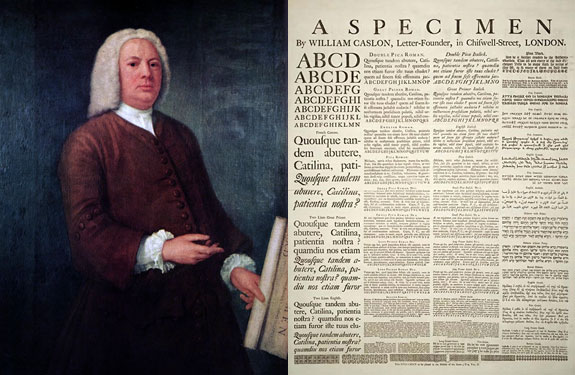

The compositor who composed on this day in 1734 the even lines of Latin prose which made up William Caslon’s first specimen sheet no doubt considered the task quite ordinary, such was the level of literacy of most of the printers of that period. His employer, the typefounder William Caslon, had started something however which was to plague type specimens for well over a century.

“Quosque tandem abutere, Catalina, patientia nostra?” The Ciceronian quotation might have been a standard element in the education of generations of youths, but eventually printers became disenchanted with it, even after it had appeared in the specimen books of all the great typefounders from Caslon to Bodoni, all of whom slyly took advantage of the rich curves prevalent in Latin prose, the better to show off their wares. Here in the United States the first specimen book to appear—that of Binny & Ronaldson dated 1812—followed the leadership of their transatlantic brethren.

The famed bibliographer, Dr. Dibdin, took issue with the practice, citing it as a deception:

“The Latin language, either written or printed, presents to the eye a great uniformity or evenness of effect. The m and n, like the solid sirloin upon our table, have a substantial appearance; no garnishing with useless herbs, or casing in coat of mail, as it were, to disguise its real character. Now, in our own tongue, by the side of this m or n, at no great distance from it, comes a crooked, long-tailed g, or a th, or some gawkishly ascending or descending letter of meagre form, which are the very flanking herbs, or dressings of the aforesaid typographical dish, m or n. In short, the number of ascending or descending letters in our own language, the p’s, l’s, th’s and sundry others of perpetual recurrence, render the effect of printing much less uniform and beautiful than in the Latin language. Caslon, therefore, and Messrs. Fry & Co., after him, should have presented their ‘Specimens of Printing Types’ in the English language, and then, as no disappointment could have ensued, so no imputation of deception would have attached.”

It may be remarked that the garrulous Doctor, a great admirer of Giambattista Bodoni, refrained from mentioning the equal guilt of the Parma typographer in this “deception.”

American typefounders, when they discarded Cicero, resorted to the phraseology of the marketplace. Instead of depending upon resounding Latin prose, they became cute, although it must be admitted that many of the 19th century specimen books remain a monument to the skills of the advertising copywriter in his embryo stage.

The simple alphabetical sentence, “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog’s back,” became in a specimen book of the Keystone Type Foundry, “Dalmatian greyhounds leaping over the fence and field reynard,” a phrase which was preceded by “Frolicksome Maltese kitten frisking recklessly through blooming flower beds.”

Realizing, perhaps, that even the Latin quick brown fox is superior to such variegated prose, the modern typefounders are primarily content to show simple alphabets.