January 29

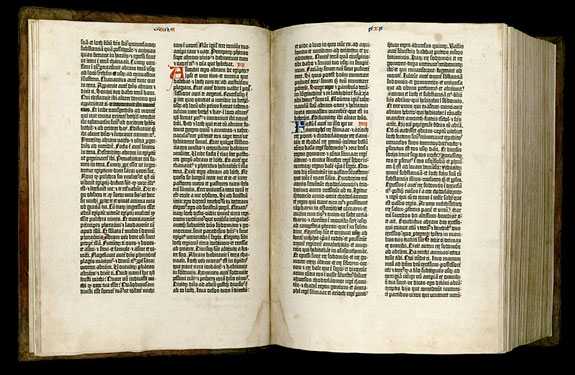

At 10 o’clock on this Monday morning in 1951, three men drove a station wagon to the Idlewild Airport in New York City. One of these men was a Customs broker. He was equipped with a set of pre-entry forms by which he expected to appease the Customs officials sufficiently to bring about the release of a suitcase which had been locked in a cargo shed of British Overseas Airways Corporation the previous Saturday. In the suitcase were the two volumes of a bible, composed in two columns of forty-two lines each and consequently known to bibliophiles as the 42-line bible, although perhaps more widely known as the Gutenberg Bible.

The story of how a Gutenberg Bible happened to be in such lowly surroundings began in December, 1950 when a hitherto unlocated copy of the book had been discovered in a private library in England. This copy had been acquired by Sir George Shuckburgh, Bt., during the 18th century, and had last been mentioned by Thomas Frognal Dibdin, the well-known bibliophile, in 1824. It had come down through various female lines until the knowledge of its existence became known to the booksellers, Quaritch‘s of London. By a coincidence, just three months prior to this discovery, an American lady had commissioned Scribner’s in New York to find a Gutenberg Bible. This was a rather difficult order to fill, since there were then but forty-seven known copies.

Mr. John Carter, Scribner’s representative in England, concluded an agreement with the book’s owner and on January 20th he brought it to the Quaritch shop in Grafton Street. There upon examination it was determined to be a fine copy, lacking but five of the 643 leaves of a complete copy. It was taken to the British Museum to compare it with the Grenville and George III copies there. The examination was halted at five o’clock when the Museum closed and resumed again on Monday morning, the 22nd. At three o’clock in the afternoon the comparisons were completed and Scribner’s office in New York notified. Carter received orders the following day to bring the bible to New York in the utmost secrecy.

On the 26th at 4:30 p.m., Carter packed the two volumes into an old suitcase, and presented himself to the B.O.A.C. office at the London airport, where airline officials took a dim view of considering the six pound bag to be personal luggage to accompany the passenger. When it was stated firmly that no bag, no passenger, the matter was resolved satisfactorily. At 6:00 p.m., the first airplane to be honored by the passage of a Gutenberg Bible took off for New York via Iceland. At Idlewild, in spite of the remonstrances of a Scribner representative, the bible was refused entry to these United States under the rule that any commercial object valued at over $500 requires a “pre-entry form.”

A few minutes later the bible was locked in a cargo shed, and bookman Carter was imbibing a double Bourbon. On the 27th, the armed with the proper papers, Scribner’s again attempted to retrieve its most valuable property. There was a slight delay when Carter insisted upon quoting a passage from a letter in 1870 by the London bookseller, Henry Stevens, to George Brinley, the purchaser of the second Gutenberg Bible ever to cross the Atlantic:

“Pray, Sir, ponder for a moment and appreciate the rarity and importance of this precious consignment from the old world to the new. Not only is it the first Bible, but it is the first book ever printed. It was read in Europe half a century before America was discovered. Please suggest to your deputy that he uncover his head while in the presence of this great book. Let no Custom Official, or other man in or out of authority, see it without first reverently raising his hat. It is not possible for many men ever to touch or even look upon a page of a Gutenberg Bible.”

Quite naturally, the Customs’ staff was impressed, but at the same time somewhat confused. By four o’clock the book had been cleared through Customs and was on its way to the Scribner safe. The lady for whom all this effort had been made, now politely declined to purchase the bible. Charles Scribner authorized its purchase from Quaritch’s and placed it “in stock” in his Rare Book Department.

The bible, known as the Shuckburgh copy, was later purchased by George A. Poole of Chicago. Upon his death his entire library, including the Gutenberg Bible, was purchased by the Library of Indiana University.