D.B. Updike Set Standard of Great Craftsmanship

- With few type faces, Updike produced a vast amount of outstanding work.

- He was a noted scholar, historian, and writer as well as a printer.

- Updike’s Merrymount Press became famous for the quality of its work.

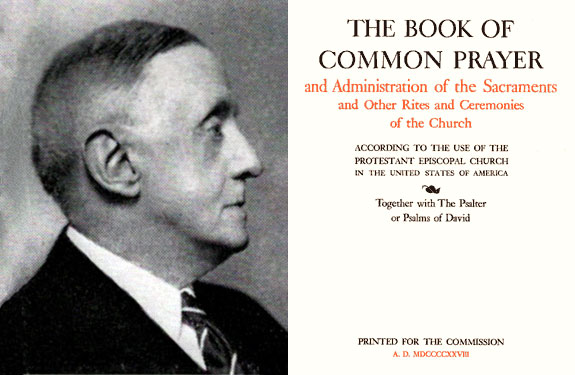

It is now 18 years since the death—in December 1941—of Daniel Berkeley Updike, American printer. In all probability these intervening years would not have been kind to the man whom Stanley Morison called, “The last and most widely influential of the notable group of Victorian writers learned in both the practice and the history of the printing and allied trades.” Economic developments in the printing industry as presently constituted would have found Updike aloof, not simply because of his own sensitive nature, but because the conduct of most successful mid-century commercial priting establishments leaves little room for the sort of individuality practiced by the great Boston printer. But however much we may claim that Updike would be an anachronism in the present-day industry, the fact remains that his work over a span of 50 years offers inspiration to every serious printing craftsman.

Had Only Handful of Types

In an era when typographers are engulfed by the tidal wave of new type designs, it is somewhat comforting to resist the pressures of typefounders by thinking of Updike’s Merrymount Press and its vast output of commercial printing, utilizing only a handful of types. Of course, advertising typography as we know it would be virtually impossible with such limited facilities, but even the job printer has so many types available to him currently that he can scarcely find the time to become well-enough acquainted with any of them to be truly effective.

It will be worthwhile, therefore, to examine the work of Daniel Updike in order to determine how his philosophy as a printer can be of help at a time when it appears that standards are difficult to maintain.

The Merrymount Press was established in Boston in 1893. Prior to this, Updike had worked for some 12 years at the offices of Houghton, Mifflin & Co., in a variety of jobs which included running errands, sorting advertising, preparing book catalogs, and finally taking a hand in planning the format of advertising and publicity material. His dissatisfaction with of work prompted him to set up office in which he planned the typography and design of books.

In the beginning he utilized the services of a man to help design the ornamentation of books. After a period he put in a supply of types, with which he supplied the additional service of composition, relying on other printers for the actual printing of the work. In this field, Updike was actually pioneering, as tade composition in the form we now know it did not become a reality until 1899. In fact, the office of typographic consultant was practically unknown. As the work load increased, he found it was necessary to install his own presses, since “without our own machines, our press-work was uneven and expensive,” Updike said.

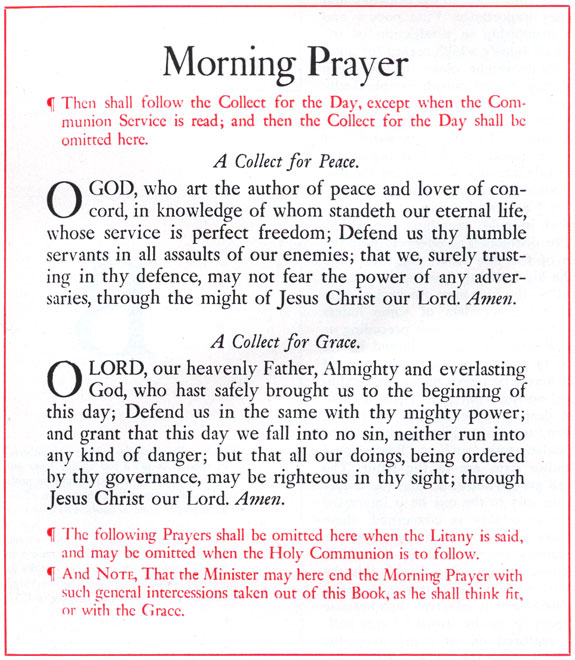

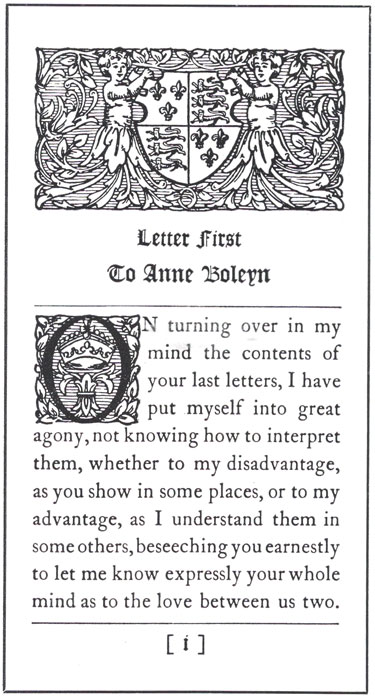

Part of a page from Updike’s edition of the "Book of Common Prayer" printed at the Merrymount Press.

The Merrymount Press soon developed a sound reputation for careful printing. It is interesting to note that Updike resisted all pressure to make his establishment a “press” in the image of the short-lived private presses of the period. In fact, many a present day jobber can take note of Updike’s aims, as stated in the bibliography of the press in 1934, “. . . a simple idea had got hold of me—to make work better for its purposes than was commonly thought worthwhile. . . .”

Produced 14,000 Printed Pieces

The extent to which he succeeded is obvious when we examine the output of the Merrymount Press. In the same bibliography Updike lists some 14,000 pieces of printing as having issued from the press in a 40-year period, which is certainly not a dilettante effort.

In an address following Updike’s death, Stanley Morison—the great typographic historian—stated that “The Merrymount Press may be said without exaggeration . . . to have reached a higher degree of quality and consistency that that of any other printing-house of its size, and period of operation, in America or Europe.”

All of this indeed, with a staff of seldom more than 30 persons at the height of its operation, and with typesetting by machine being produced only in its last few years. This machine happens to have been the Monotype machine, and the first type which Updike machine-set was Times New Roman. He was the first American printer to acquire the letter.

Relied Mainly on 15 Faces

The types which bore the brunt of Merrymount printing were Caslon, in a late 18th century cutting, a Scotch Roman, Mountjoye (now called Bell), Janson, Oxford, French Oldstyle, Bodoni, Poliphilus (Series 170), and Lutetia. Two privately cut letters were Montallegro and Merrymount, the latter having been cut by Bertram Goodhue, originator of Cheltenham. The collection was rounded out by a French script, and three blackletters.

It may be noted that although Updike acquired the Janson type in 1903, there is no mention of the designer, Anton Janson, a 17th century Dutch punch cutter, in the famous two-volume work, Printing Types, Their History, Forms and Use, which is universally recognized as the standard work on the history of type. Updike produced this great study in 1922, from his notes as a lecturer on printing at Harvard School of Business Administration a few years earlier.

Printing Types is undoubtedy the greatest single work on type to be written in this country. Morison has stated, “Printing Types remains absolutely essential to the understanding of the subject.” The two-volume work was hand-set in the Oxford type at the Merrymount Press and published by the Harvard University Press. The book is still in print in an edition revised by Updike in 1937.

Two other short volumes of essays are valuable as an insight to Updike’s character as a printer—In the Day’s Work, published in 1924, and Some Aspects of Printing, Old and New, published in 1942.

The product of the Merrymount Press has been divided into several groups, book printing being the most important. In this field Updike gave particular attention to liturgical books. His edition of the Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal church, printed in 1930, is considered to be one of the finest products of the press and of American printing.

During the early years of its existence, the press printed many trade books. Although the volume of this work tapered off, every year a few trade editions were printed. In the production of privately-printed books and limited editions, the press was particularly successful, as was the large amount of work done for colleges and institutions. The balance of the output consisted of numerous pamphlets, keepsakes, and announcements, all bearing the stamp of Updike’s careful personal attention.

One of his primary reasons for opposing the rapid expansion of a successful business was the simple fact that it would become impossible to keep up with every job that was accepted for printing.

Printers today can draw inspiration from the example of this New Englander who gained lasting fame as one of the finest of American printers. His own esthetic principles, of course, supplied the essential character to his business associations, but in addition he quietly applied a set of standards of operation which he refused to compromise.

He made it a point to develop a learned judgment concerning his work. In addition to his contributions as a printer, he continued in the line of Theodore Low De Vinne as a typographical scholar, adding luster to American scholarship in this field. However, it is as a printer that his example is most important, since with what we now consider to be limited resources, he left us an outstanding body of work, which American printers can continue to take pride in.

This article first appeared in the January 1960 issue of Printer and Lithographer.

[…] a favorite. So without further ado, from the January 1960 issue of Printer and Lithographer, is “D.B. Updike Set Standard of Great Craftsmanship.” | Email This Post « February 2 D.B. Updike Set Standard of […]