January 5

“Eureka!” exclained a former compositor named Sam Clemens, at 12:20 p.m. on this day in 1889. The esteemed author and humorist, Mark Twain, then went on to say, “At this moment I have seen a line of movable type, spaced and justified by machinery! This is the first time in the history of the world that this amazing thing has ever been done.”

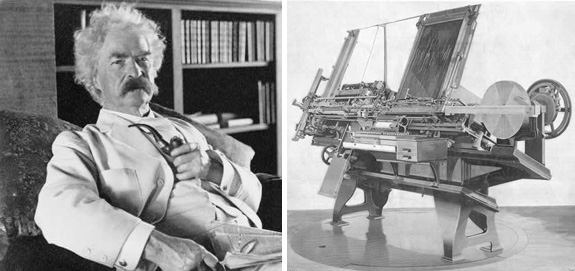

The “dam typesetter” to which Clemens was referring was the machine known as the Paige Compositor, the brain-child of an eccentric Rochester, New York inventor named James W. Paige, called by Twain “a most extraordinary compound of business thrift and commercial insanity.” Mark Twain over-evaluated his own business acumen and for too many years was involved in a variety of ventures, all of which cost him money. While his ordinary enthusiasms generally relieved his pocketbook of only twenty to thirty thousand apiece, the Paige experiment cost him according to most accounts, close to a quarter of a million dollars and was the direct cause of the bankruptcy of his publishing business.

At a period when tremendous enthusiasm was being generated by the concept of automating the compositor, Paige’s ideas seemed to Mark Twain to represent the highway to great wealth. A contemporary wrote that “he covered pages with figures that never ran short of millions, and frequently approached the billion mark.”

In a letter to his brother, Orion Clemens, Mark dwelt upon the marvels of his new toy, saying, among other things, “This is indeed the first line of movable types that ever was perfectly spaced and perfectly justified on this earth. This was the last function that remained to be tested—and so by long odds the most important and extraordinary invention ever born of the brain of man stands completed and perfect. . . .

“But’s a cunning devil, is that machine!—and knows more than any man that ever lived. You shall. We made a test in this way. We set up a lot of random letters in a stick—three-fourths of a line; then filled out the line with quads representing 14 spaces, each space to be .035ʺ thick. Then we threw aside the quads and put letters into the machine and formed them into 15 two-letter words, leaving the words separated by inch vacancies. Then we started up the ma-chine slowly, by hand, and fastened our eyes on the space-selecting projected its thud pin as the first word came traveling along the raceway; second block did the same; but the block projected its second pin.

“Oh, hell! stop the machine—something wrong—it’s going to set a space!” General consternation. ‘A foreign substance has got into the spacing plates.’ This from the head mathematician.

“Paige examined. ‘No—look in, and you can see there’s nothing of the kind.’ Further examination. ‘Now I know what it is—what it must be; one of those plates projects and binds. It’s too bad—the first test is a failure.’ A pause. ‘Well, boys, no use to cry. Get to work—take the machine down.—No—Hold on! don’t touch a thing! Go right ahead! We are fools, the machine isn’t. The machine knows what it’s about. There is a speck of dirt on one of these types and the machine is putting in a thinner space to allow for it!’

“All the other wonderful inventions of the human brain sink pretty nearly into common-place contrasted with this awful mechanical miracle. Telephones, telegraphs, locomotives, cotton gins, sewing machines, Babbage calculators, Jacquard looms, perfecting presses, Arkwright’s frames—all mere toys, simplicities! The Paige compositor marches alone and far in the lead of human inventions.”