Anatomy of a Type–3: Caslon, Part 2

As noted last month, remodeling of earlier Dutch types by William Caslon about the year 1720 created such a wide demand for the “English” letter that, except for the period 1790–1840, it has enjoyed most universal approval.

Naturally enough, it became the principal type of the American colonial printers, most of whom depended upon England for the equipment in their printing offices. It is now of general knowledge that the most important document of American history, the Declaration of Independence, when first set in printer’s types utilize those cast by William Caslon. American printers have always been enthusiastic about the type and were responsible for much of its popularity in the years up to the Second World War.

Oldstyle or Transitional?

Under most systems of type classification, Caslon is known as an oldstyle (Old Face in England), the final development of those romans which were first cut by Nicolas Jenson of Venice in 1470. Actually, a fairly strong case can be made for calling Caslon the first widely-used transitional type, rather than the Baskerville design of 1757.

However, most typographic historians have held that Caslon’s dependence upon the 17th century Dutch types constructed a letter with more oldstyle features than are present in the transitional types.

The best-known character in the font is the cap A, with its concave apex. The cap T is another easily remembered letter, with the crossbar dropped well below the level of the serifs. A note of caution, here, though: In the first Caslon specimen sheet of 1734, the great canon (42-point) is not a Caslon original, having been cast by earlier English founders. Thus, the T in the 42-point size of the subsequent copies of Caslon follows the original, which features a T with a flat crossbar and straight serifs. In the Monotype 337 series, this feature is continued through 60 and 72-point.

The lowercase of Caslon is easily remembered by the wedge-shaped series of most of the letters, particularly noticeable in the t.

Inconsistencies in Fitting

Even in the original version and copies made by ATF, Monotype and Linotype, there are inconsistencies in the fitting and the alignment of a number of letters. Most typographers who work closely with types learn to steer clear of certain sizes of their favorite types.

In Caslon, for example, the 24-point seems to lack the grace of the 18-point, and in relation to the larger sizes appears to be considerably bolder. Due to this discrepancy, a 22-point has been cut in order to provide an “in-between.” In the Monotype 337 series, the difference between 12-point and 14-point is negligible.

Such variations have the combined effect of individuality that has apparently charmed many a typographer, unhappy about the regularity of so many pantograph-designed typefaces. Depending upon the viewpoint, these same features are often difficult to justify in attempting a judgment about why the type has been so long-lived.

New Popularity

The resurgence of Caslon type in the United States can be dated from 1858, when the Philadelphia foundry of L.J. Johnson (later MacKellar, Smiths & Jordan) brought fonts from England and duplicated them by manufacturing electrotype matrices.

The firm’s periodical, the Typographic Advertiser, in its issue of July 1859, showed thirteen sizes of Caslon. It later appeared in the 1865 specimen book of the Johnson Foundry under the name of Old Style No. 1. It came slowly in popularity, but in 1892, when Vogue magazine was restyled in Caslon type, the revival really began in earnest. It was decided to use the Johnson cutting, and the foundry received the largest type order it had enjoyed in over 30 years.

The use of Caslon in Vogue was followed by its employment by some of the nation’s best typographers, including Will Bradley. It was thus an early candidate for the composing machines then being introduced. The Monotype Company was first to make it available, in 1903, with a version based upon the Johnson type, then the property of American Type Founders.

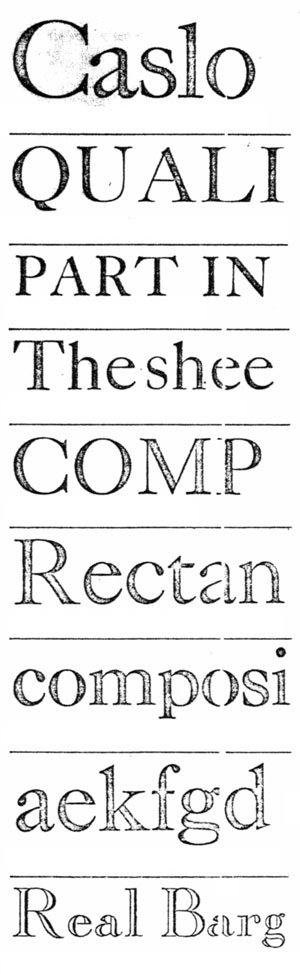

(top to bottom): Stephenson Blake's Caslon Old Face; American Type Founders' Oldstyle 471; Linotype's Caslon Old Face; Monotype's Caslon Oldstyle 337; Ludlow's True-Cut Caslon; American Type Founders' Caslon 540; American Type Founders' New Caslon; American Type Founders' Caslon 641; American Type Founders' Caslon Openface;

At the present time, there exists a number of re-cuttings of Caslon which are very close to one another. The Caslon Old Face of Stephenson, Blake & Company, is of course the original, but the ATF Caslon 471, based upon the Johnson copy, is very close indeed, as is the Monotype 337, Linotype Caslon Old Face, and Ludlow True-cut Caslon.

ATF manufacturers Caslon 540, which is basically 471 with shortened descenders, and which enables New Yorkers to recognize Gimbel’s from Macy’s (which uses 540 in its advertising).

New Caslon, oh wait which comes between the light (or regular) and boldface, is cast both by ATF and Monotype. It lacks the grace of the original, as does Monotype’s American Caslon, another medium-bold version.

Many Versions

The recently announced Caslon 641 of ATF is closely related to New Caslon, but with a number of the characters improved in design. In addition to those versions mentioned, there are many other “Caslons” available, such as Caslon Old Roman, Caslon Old Style English, Caslon Old Style Inland, and that ubiquitous but far-remove type called tongue-in-cheek, Caslon Antique.

This old reprobate, a victim of bad-timing when first introduced by Barnhart Brothers and Spindler late in the last century under the name of Fifteeth Century, did not sell at all until some ad genius, about 1918, changed its name to Caslon Antique. Although it has done very well as “Caslon,” it should scarcely be allowed in the same composing room as the fine old letter which has been the subject of this article.

There are also the usual variants such as bold condensed, openface, swash, etc., as is the case with any successful type. It would seem that Caslon is bound to survive, although even well-informed typographers have to search for reason to explain it all. In the. When everything which is traditional seems to be suspect, maybe there is nothing to worry about.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the October 1967 issue of Printing Impressions.