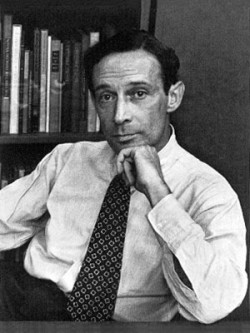

Joseph Blumenthal, Fine Printer—Part 1

Over the past half-century, many distinguished printers have had their impact upon the typography of our times. Obviously a list of such figures would include Bruce Rogers, W.A. Dwiggins, T.M. Cleland, Frederic W. Goudy, etc. But they were primarily designers who were never content to settle down to the every-day routine of running a printing plant. The most notable exception, of course, would be Daniel, Berkeley Updike, proprietor of the Merrymount Press in Boston.

Over the past half-century, many distinguished printers have had their impact upon the typography of our times. Obviously a list of such figures would include Bruce Rogers, W.A. Dwiggins, T.M. Cleland, Frederic W. Goudy, etc. But they were primarily designers who were never content to settle down to the every-day routine of running a printing plant. The most notable exception, of course, would be Daniel, Berkeley Updike, proprietor of the Merrymount Press in Boston.

Of those individuals who have taken on the management responsibilities of an entire shop, Joseph Blumenthal of the Spiral Press in New York City has earned for himself a solid place among fine American printers.

As a young man excited about printing, he naturally enough looked to some of the fine printing plants of the 1920’s as a source of inspiration, giving direction to his own plans for the establishment of a office that would allow full scope to his own concepts of excellence.

He had received his initial introduction to the world of print in a publisher’s office in 1924, after attending Cornell. In 1925, he took a European trip, during which he saw so many examples of fine printing that he decided to become a printer.

His first opportunity to become intimately involved with the Black Art was a stint of a few months duration as an unpaid helper in the famous establishment of William Edwin Rudge in Mount Vernon. New York. This most fortuitous beginning was followed by still another wageless experience, this time for the redoubtable Hal Marchbanks in New York City.

To be a printer was now uppermost in his mind. He lost time in taking the steps to set up his own printing plant. In 1926, with the purchase of about a hundred pounds of type and, a treadle platen press, the Spiral Press came into being. Because of the cultural instinct of its owner, however, this tiny establishment didn’t begin with the printing of a letterhead for a grocer, but for its first item produced an entire book in an edition of 350 copies. Titled Primitives, it contained poems and wood blocks by the artist. Max Weber.

Full of enthusiasm, Blumenthal now began the serious effort necessary to make his shop a full-time effort. Fortunately he solicited publishers. art galleries and museums rather than the small businesses more commonly sought by a one-man plant. This thoughtful approach helped him to become solidly established. With improved prospects, he took as a partner George Hoffman, then superintendent of the Marchbanks Press, and began immediately to acquire equipment more suitable for the kind of work he was soliciting.

Anyone who attempted to break into fine printing during the 1920’s naturally enough had as a guide America’s most famous printing plant, Updike’s Merrymount Press. Blumenthal has often stated that Merrymount was indeed a model in the early days of his own press. That he and the Boston printer had equal standards is obvious as Updike, when asked about the goals of his press, noted that he “wished to do common work uncommonly well.”

Blumenthal has written of the credo of Updike and in his own career has attempted to follow it carefully. That he was completely successful is evident. While producing many fine books over the forty years of its existence, the Spiral Press also turned out the countless items which make up the daily life of any reasonably small shop—10,000 of them in fact, from bookplates to broadsides. ,

An examination of Spiral’s run-of-the-mill work is revealing. The guiding hand of a first class printer imbued with the continuing traditions of his craft is very evident. Every printer has upon occasion found it necessary to question a customer’s judgment in some of the work to be produced, and has had to determine whether he wished to accept those jobs that failed to meet his standards. Blumenthal admits to such rejection but says that in his case it was infrequent. There is no doubt that Updike was more imperious in this respect.

In any discussion of fine printing there remains always the question of definition. Joseph Blumenthal has presented his own viewpoint on the interpretation of the differences among private printing, fine printing and commercial printing. He has stated: “The private press makes and issues books at the pleasure of its owner. Fine printing is printing done with some artistry in the planning and design, and with that combination of knowledge, skill, and devotion which are the inherent components of craftsmanship. The owners of such printing shops normally depend on their work, in whole or in part, for their livelihood . . . Money is a necessary corollary but never a prime objective. For the commercial printer, money is the prime, and perhaps too often the sole, objective . . . The average printer has become a machine owner who sells the machine’s time and productivity to any buyer thereof. These definitions are not, of course, inclusive. They are generalizations with the limitations of all generalizations, and with allowance for overlapping.”

While slowly establishing his reputation, Blumenthal never lost his abiding interest in printing history and in this respect has been an honored figure in American typography for some fifty years. He also became involved in the design of type, as he wished to have a type that would be exclusive to the Spiral Press. While he could readily have commissioned Frederic Goudy, then at the peak of his influence, Blumenthal decided instead to design his own type.

He took a set of drawings to Germany in 1931, where they were cut into punches by Louis Hoelle. The Bauer foundry at Frankfurt then drove the matrices and produced the type which was named Spiral. It had sufficient quality to attract the attention of the astute Stanley Morison who had acquired it for the Monotype Corporation of London, which then issued the face with a new name, Emerson, in 1935. It was cited most favorably in a review by the distinguished calligrapher. Reynolds Stone, who wrote that it “avoided the rigidity of a modern face and preserved some of the virtues of the classic Renaissance types.”

Some of the finest books produced at the Spiral Press have been set in Emerson. Several years ago Blumenthal donated the original punches of Spiral to the School of Printing at Rochester Institute of Technology, and this year he added the matrices. While he has admitted that the face was not a financial success, and therefore “a spectacular failure,” many a typographer would be very happy to have such a fine letter available in quantity in his cases.

In 1930 Blumenthal designed and printed Robert Frost’s Collected Poems, which brought him into the poet’s circle of friends. This relationship resulted in a lone series of

Christmas books of Frost poetry, and the subsequent design of a number of important Frost books, of which the poet stated, “Spiral’s typography and printing found things to say to my poetry that hadn’t been said before.”

While the Press has now ceased operations, the influence of its proprietor continues. We are witnessing the emergence of an important typographic historian, since Joseph Blumenthal at the age of eighty remains fit and is eagerly turning his attention to the interpretation of our past, a task for which he is preeminently fitted. Next month I would like to continue this short review of the contributions of an outstanding American printer.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the October 1977 issue of Printing Impressions.