The Grabhorn Era—Fine Printing In the Far West

“It’s the end of an era.” Well, here is a statement made so frequently about so many events plaguing our civilization during the last 30 years that it has become a rather tired cliché. But, upon occasion, it is the only thing which can be said about occurrences that leave us at a loss for words.

“It’s the end of an era.” Well, here is a statement made so frequently about so many events plaguing our civilization during the last 30 years that it has become a rather tired cliché. But, upon occasion, it is the only thing which can be said about occurrences that leave us at a loss for words.

And when the banality is used by an articulate and astute person such as Jackson Burke, former director of typography for Mergenthaler Linotype Co., it is probably the sentiment of most of the rest of us. What prompted Burke’s remark was the death, on June 14th, of an American printer, Robert Grabhorn of San Francisco, who along with his brother Edwin will appear on any list ever to be compiled of great printers who have practiced their art in the United States.

If we can look to the California printers as being the most representative of the craft, as such luminaries as Daniel Berkeley Updike, Bruce Rogers, Frederic W. Goudy, et al., all of whom have been mentioned from time to time in this department, then the Westerners can confidently regard the brothers Grabhorn as being most representative of typographica california.

And this is not an accolade which can be lightly bestowed when we remember the printers who have made their reputations in California. John Henry Nash comes first to mind, of course, and while there has never been complete agreement about him as an individual, he was unquestionably a first-rate printer, even without being called the San Francisco Aldus.

There’s Lawton Kennedy, considered by many to be the finest pressman who has yet practiced on these shores. Ward Ritchie, Saul and Lillian Marks of the Plantin Press, Dorothy and Lewis Allen, and many more printers who have sought to continue the traditions of the historic craftsmen.

The opportunity to serve this tradition is no longer viable economically. Sad to relate, it is probable that very shortly only a handful of printers will have the interest in maintaining high standards in the fine printing of books. Simply because they won’t be able to find the customer who not only knows what he is after but is quite willing to pay for it.

It might appear to be extraordinary that a couple of printers named Edwin and Robert Grabhorn could represent an era, but when we consider the output of their press between 1919 (when it was established in San Francisco) and 1965, no other term will suffice. Of course that “era” really began to subside in the post-World War II period. Historians of all stripes, when they sum up the present century, will undoubtedly pinpoint with greater accuracy the time when American attitudes underwent basic changes. In this respect there is general agreement that the economic depression of the Thirties, followed by the cataclysm of the War, altered the more buoyant outlook of most Americans.

The Grabhorns were most fortunate to establish their reputations while the market in fine printing was fairly solid, and they were thus able to continue their productive lives past the age when most of us are considering retirement. This is not to say that they didn’t have economic problems during that half century. But for one thing, they never had ambitions to be “large and successful.” Most of the time they worked by themselves or with one or two assistants, even though every young fellow who fancied himself another Updike knocked on the Grabhorn door for admittance to apprenticeship, with no room, board, or even wages expected by any of them.

In the beginning the brothers were advertising typographers, but as both of them were book collectors, they turned in mutual preference in the direction of book printing, in spite of the lucrative business they had built as ad typos. Their approach to the production of books was whimsical to say the least. They never “designed” a book, but tended to let it grow a bit at a time. What type did they have a particular feeling for at the moment. What paper would be right for the type, or vice versa? The illustrating and the binding were also shop functions, in most instances.

But it all worked, because they loved to experiment and because they simply loved to make books. Hand-set type was the standard. They used several of Fred Goudy’s types and undoubtedly some of the finest books ever produced with his types were set at the Grabhorn Press. One of the Goudy types, originally called Aries, which was a face in the spirit of the 1465 Subiaco type of Pannartz and Sweynheym, was sold to the Grabhorns as their exclusive type. Renamed Franciscan, it was used for many notable books, the foremost of which were the two great bibliographies of the work of the Press.

Perhaps the attitude of the brothers toward type can best be understood by the story of the production of Leaves of Grass, possibly the greatest work of the firm. Their first choice was the Dutch type Lutetia, which was purchased in quantity. After the printing of scores of pages, the Grabhorns decided that Lutetia was a bad choice for Whitman, so the hell with it. Out it went, and they started all over again with Goudy Newstyle. The result stands on its feet as the most splendid edition of Whitman ever produced and one which the printer-poet himself would have thoroughly understood and enjoyed.

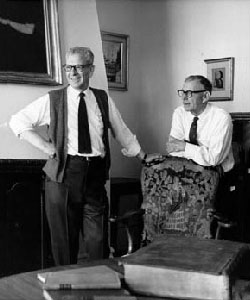

Edwin (1889–1968) and Robert (1900–1973) were scholars of printing in addition to being practical printers. While they occasionally produced allusive volumes intended to portray some specific typographic style, they really preferred to be innovators, as anyone who takes the time to look at their books will discover immediately.

The most complete collection of Grabhorn books is in the San Francisco Public Library, naturally enough, but many libraries have been astute enough over the years to purchase them as examples of fine printing, a term which I’m afraid I overuse in this short tribute without really explaining what it is. Perhaps that will come at another time.

Hopefully, someone will put together a complete account of the Grabhorns and their great contribution to the printing of books in our time. It is further to be hoped that this account will be written by a person who loved and admired them as individuals in addition to recognizing their status as printers. Perhaps out of it will come a few understandings of what their lives can mean to those of us who for a variety of reasons are devoted to some of the same concepts which motivated them as creative printers.

So we can say that it is the era of the Grabhorns which has ended, but with such inspiration for guidance, who can say that the era of fine printing is over?

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the October 1973 issue of Printing Impressions.