January 18

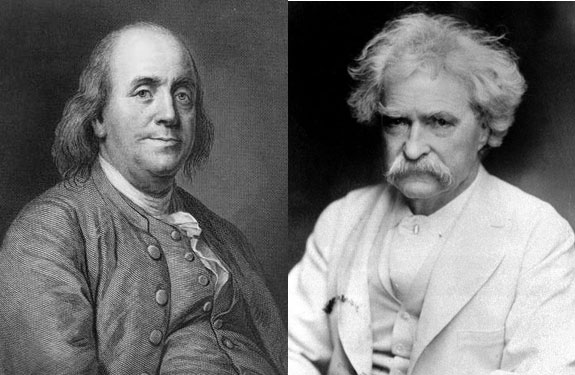

The Typothetae of the City of New York met on the evening of January 18 in 1886 to honor two printers, Benjamin Franklin and Mark Twain. The white-shirted audience who attended the affair, held at the grand old restaurant, Delmonico’s, ostensibly to honor Dr. Franklin, was not above allowing the humorist to share the proceedings, particularly when he could indulge in his reputation as a raconteur.

The former Missouri swift did not disappoint his listeners as he regaled the group with nostalgic tales of his youth as a country comp.

“I wetted down the paper Saturdays,” he remarked, “I turned it Sundays—for this was a country weekly; I washed the rollers, I washed the forms, I folded the papers, I carried them around at dawn Thursday mornings. The carrier was then an object of interest to all the dogs in town. If I had saved up all the bites I ever received I could keep M. Pasteur busy for a year!”

Mark’s reminiscences of his type-sticking days generally gave the impression that he had few equals as a compositor, although this ideal image was not born out by some of his contemporaries. One of these worthies, Anthony Kennedy, knew Sam Clemens as a young fellow remarkable only that he didn’t drink whisky, a conspicuous oddity for any comp in the mid-fifties of the last century. Kennedy disclosed in 1903 that when the other compositors were making twelve dollars a week, at thirty cents per thousand ems, “it was all Sam Clemens could do to make eight or nine dollars. He always had so many errors marked in his proofs that it took most of his time correcting them. He could not have set up an advertisement in acceptable form to save his life.”

Compositor Kennedy might have added, of course, that while Mark’s fellow typos could have set circles around him, none of ’em could have written Huckleberry Finn.

Actually, in a letter written in 1853, and published by the Hannibal Daily Journal on September 10th, Mark deprecated his ability, but this was long before he was a famous man. He wrote, “The printers here in New York are badly organized and therefore have to work for various prices. These prices are 23, 25, 28, 30, 32, and 35 cents a 1,000 ems. The price I get is twenty-three cents; but I did very well to get a place at all, for there are thirty or forty—yes, fifty good printers in the city with no work at all; besides my situation is permanent and I shall keep it till I can get a better one!”

The letter went on to describe the working conditions of the period. Twain noted the perplexing problems of a country printer trying to hold a job in the big town.

“The office I work in is John A. Grays, 97 Cliff St., and, next to Harper’s is the most extensive in the city. In the room in which I work, I have forty compositors for company. Taking compositors, pressmen, stereotypers, and all, there are about 200 persons employed in the concern. . . . They are very particular about spacing, justification, proofs, etc., and even if I do not make much money, I will learn a great deal. I had thought Ustick was particular enough, but acknowledge now that he was not old-maidish. Why, here you must put exactly the same space between every two words, and every line must be spaced alike. They think it dreadful to space one line with three-em spaces, and the next one with five ems.”