Printer as Historian: The Story of D.B. Updike

“What bliss it were to be reading it for the first time!”

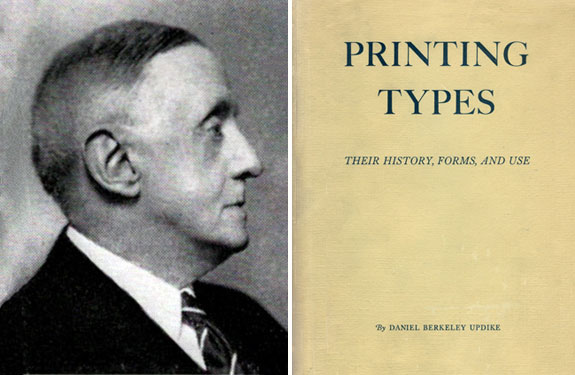

The late Lawrence C. Wroth, distinguished American bibliographer and printing historian, so ended his preface to the third edition of Printing Types, Their History, Forms, and Use, A Study in Survivals, by Daniel Berkeley Updike, which appeared in 1962. The first edition of what can only be termed a seminal work in the history of printing was first published a half century ago, in 1922, by Harvard University Press.

Printers the world over owe a debt of gratitude to the Press for keeping the two-volume work in print during this long span of time in which typography has been subjected to many of the strains affecting the civilization itself in the same period.

Well Received

Quite possibly the paean of praise which greeted the publication of Printing Types was so formidable that the work enjoyed the willing lip-service of a host of purchasers. However it suffered the fate of numerous other generant texts in remaining on the bookshelf, lamentably unread. But, like Gibbon and the Bard, it was always projected for that holiday or winter-night reading which just never seems to get into the schedule.

Certainly a book containing 518 pages, accompanied by 367 illustrations, most of them full-page and independent of the numbered pages, appears at first glance to be “monumental,” as it was so described in the first review. Stanley Morison, then just 33 years of age and about to come into his own as a typographic historian, began his review in Volume 1 of The Fleuron: “. . . the most important addition to die literature which has appeared for many generations.”

Writing in 1947 in a memorial volume to Updike, Mr. Morison indicated that he had not changed his mind: “Despite the immense amount of research that has been done since, and which Updike’s work was designed to inspire, Printing Types remains absolutely essential to the understanding of the subject; and, as far as the intelligent appreciation of printing style is concerned, every bit as valuable as it was 20 years ago.”

Merrymount Press

Daniel B. Updike was first of all, a printer. As proprietor of The Merrymount Press in Boston, he had, prior to 1922, established a reputation for sound and traditional typography. Like Theodore Low De Vinne before him, he had also developed a scholarly attachment for his craft in addition to a solid understanding of the practical factors of everyday printing production.

Unlike De Vinne, however, he had never served a printing apprenticeship. It is doubtful if he ever set a line of type in his life, nor did he ever operate even the simplest press. But he was no dilletante printer, even though he depended greatly upon the employees of The Merrymount Press, in particular John Bianchi, the man who became his partner.

In the period 1911–1916, Updike lectured upon the history of printing before classes of the School of Business Administration of Harvard University. At the suggestion that his notes for this course be constructed into a book, Updike—with a great deal of editorial assistance,—completed the manuscript after several years of painstaking work. It was John Bianchi who recommended that the book be illustrated. Updike agreed, but the difficulty in obtaining the proper illustrations held up publication until 1922. All authorities concede that it is the combination of text and illustration that contributed so much to the success of the work.

Inspiration for Printers

Printing Types is a great book. The timing of its issue was of course favorable, there not having been such a work in typography since De Vinne’s Plain Printing Types of 1900. While it has inspired two generations of printers, its erudition has undoubtedly prevented later scholars from attempting to emulate its achievement, at least upon such a broad canvas. Mr. Morison’s eminence as a typographic historian rests primarily upon short essays, except for that last superb undertaking, John Fell, published the day following his death in October 1967.

Updike departed from the usual practice of printing histories by including precise details concerning the manufacturing of printing types, the development of the point system, and such matters usually left to the manuals of printing, which in their turn treat printing history all too casually.

The reader of Updike may find himself overwhelmed by the titles of German, Italian, and French books, but he will quickly discover that the historian is more deeply concerned with the types in which the books are composed, discussing these in considerable detail, complemented by the matchless array of type specimens offered in the illustrations.

As He Saw the 19th Century

In view of the enlightened scholarship so evident in the pages of Printing Types, it comes as a great surprise to the contemporary reader that Updike closed his eyes to what is now considered one of the most exciting periods in typographic history—the 19th century. The demands made upon the printer by the manufacturing industries created by the industrial revolution brought about a typography which was no longer dominated by the art of the book; instead, the printer was enlisted as a partner in the promotion of the sale of products. Here was a new challenge.

The typefounders, beginning in 1816, met it with enthusiasm, issuing types which were designed primarily to attract attention. By the middle of the century, the requirements of commercial printing completely dominated the production of the foundries, in Europe and in the United States.

The uninhibited types of this era—the sans serifs, the square serifs and clarendons, the extrabold versions of modern romans—coupled with the more exuberant forms such as the Tuscans, the shadowed and outline types, and other embellished styles, all combined to divert the printer from the traditional forms which had dominated the first 350 years of the art.

To these “market-place” letterforms, Mr. Updike gives short shrift indeed. His only mention of them occurs in his chapter on English Types: 1800–1844, in which he refers to them as “hideous fashions.” He quotes the London printer, William Savage, who wrote that such bad types “may be attributed to the bad taste of others, whom the founders are desirous of obliging.”

Thus, the student of typography in the 1970s will look in vain in Updike for enlightenment upon the decorative forms of the last century. While this is undoubtedly a shortcoming in such an all-inclusive work, it should not at all interfere with the pursuit of typographic distinction to which Updike dedicated his life. Today there are several texts which treat the 19th century in detail, although none of them bring to the task the historical objectivity which the Boston printer brought to his study of the early types.

Five Centuries of Printing

No reader who seriously approaches Printing Types can ever come away disappointed. Here is the consummate tribute to excellence over a 500-year period of the printer’s craft—one that is bound to mature the judgment and appreciation for first-rate typography of everyone who makes the effort to understand that long and arduous road traveled by the scholar-printers of the past.

Almost every writer who discusses Updike seems to wind up by quoting the last paragraph of Printing Types, which begins, “The practice of typography, if it be followed carefully, is hard work. . . .” I prefer to choose a few other sentences from that last chapter in which he was attempting to express his creed as a printer: “The outlook for typography is as good as ever it was—and much the same. Its future depends largely on the knowledge and taste of educated men. For a printer there are two camps, and only two, to be in: one, the camp of things as they are; the other, that of things as they should be. The first camp is on a level and extensive plain, and many eminently respectable persons lead lives of comfort therein; the sport is, however, inferior! The other camp is more interesting. Though on an inconvenient hill, it commands a wide view of typography, and in it are the class that help on sound taste in printing, because they are willing to make sacrifice for it. This group is small, accomplishes very little comparatively, but it has one saving grace of honest endeavor—it tries.”

After 50 years, this is still sound advice, especially in this era of typographic uncertainty. Perhaps it’s time to haul Updike off the shelf again!

A last observation concerns the type in which the book is composed, entirely by hand as were so many of The Merrymount Press books. It is set in Oxford,which was first issued as Roman No. 1 of Binny & Ronaldson of Philadelphia. It was issued later by American Type Founders;. As this face made its first appearance in B & R’s 1812 Specimen Book, it is one of the earliest American types.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the January 1972 issue of Printing Impressions.

Further Reading

On Re-reading Updike by A.F. Johnson.

Volume 2 of Printing Types, Their History, Forms, and Use, A Study in Survivals by Daniel Berkeley Updike.