Scripts and Cursives Widen Typographical Horizons

- Wide range of sizes and styles gives typographer more leeway in design

- New designs offer small printer chance to achieve “hand-lettered look”

- Key to classifying scripts and cursives lies in historical development

During the last few years, the foundries of the world have been remarkably busy producing new script types. Undoubtedly, this popularity has resulted from the success of hand-lettering and photolettering, both of which have contributed to the present interest in freely drawn pen or brush hands.

Before discussing the current crop of new types in this genre, it might be advisable to outline the classification of scripts in general. While some printers still use the term “script ” for all the faces in this group, a broad breakdown is more desirable for purposes of simplification.

It is common to refer to scripts as types which the letters are connected, and to use the term “cursive” to indicate a type which retains the script form but with separate characters. Although this division is sufficient in most instances, typographers prefer to classify still farther by differentiating between those letters which are drawn with a broad pen and those with brush strokes.

Historical Background Important

Such a system of classification will be valuable to the person seeking an introduction to types, but he will soon learn to dig deeper for more rapid method of pin-pointing any script under consideration. For that, it is necessary to turn to the historic development of scripts and cursives, although only a hint of the involved source material can be outlined here.

The very beginnings of the craft, printers it made attempts to capture the freedom of handwriting. The first italic type, cut for the House of Aldus in 1501, endeavored to capture the grace of the slanted humanist hand. In the present day this is been most successful in types which are purely italic rather than The name given to this fifteenth century Italian manuscript hand was Chancery. Under that term we can list a number of excellent copies of that letter available today, such as Arrighi and the italics of Palatino, Trajanus, Deepdene, Lutetia, and Weiss.

From the Chancery hand, writing went through a period of change in various parts of Europe, reverting from the broad and today flexible point which gave a closer imitation of the engraver’s tool. The first cursive type on record, is Civilité of Robert Granjon, was produced in France about 1560.

Writing style was set by merchants, who employed clerks to copy all business transactions. As a writing hand became popular, it was frequently copied by type cutters. Well into the seventeenth century, Dutch scribes influenced writing styles. In England, this writing developed into English round hand. Here is an important source of many contemporary script faces, such as Typo Script, Bank Script, and Commercial Script.

With English round hand, the historical influence on script types comes to an end. We can therefore organize our scripts and cursives into these rather loose sections: Chancery, broad-pen or calligraphic, and round hand. Many of the smart styles of today derive from the inspiration of the artist rather than from a particular source. They are formed, of course, by the tool used for the lettering. Because modern hand-letters use brush-drawn characters a great deal, type founders have issued many types with this characteristic.

New Interest in Calligraphy

Revival of interest in calligraphy has contributed materially to the popularity of script types. From almost every country the steady stream of new designs continues. The small printing office, since it can seldom afford hand- or photolettering in a short-run job, is most interested in script types. With them, the printer can match the smart appearance of advertising done by first-rate lettering artists. This discussion is therefore directed toward the small printer who is interested in the variety of types now available.

In the United States, American Type Founders has added, within the last few years, for new designs to the catalog of scripts: Brody, a bold-weight letter in a popular hand-lettering style; Repro Script, and interesting monotone medium-weight script into calligraphic takes, Thompson Quillscript and Heritage, the latter of particular interest to the printer of announcements.

Despite the fact that slug-casting machines do not lend themselves to the script form, the Ludlow slanted matrix gives that firm an opportunity to offer script letters occasionally. The most recent of these is Admiral, designed by the creator of many successful Ludlow types, R. Hunter Middleton.

From the European countries we have a veritable flood of new designs. Some of them will appear to American printers; others will be regarded with little enthusiasm. It must be remembered that the prevalence of good hand-lettering in this country has made printers here realize what constitutes a good script letter. Of course, novelty types will always be in demand, but they will have to conform to American standards if offered for sale in this country.

The Berthold foundry in Germany has produced in the past two years some half-dozen new cursives in a wide range of styles. Boulevard is a type which follows the French Batarde types of the eighteenth century. Caprice is a light broad-pen cursive. Pallete, a bold-face type, is close enough in form to be almost a bold version of Caprice, while Derby and Dynamic are both bold-face cursors, quite well-drawn. Rainy here Black, the newest Berthold type, is an extra-bold letter with no particular interest, I believe, to American printers.

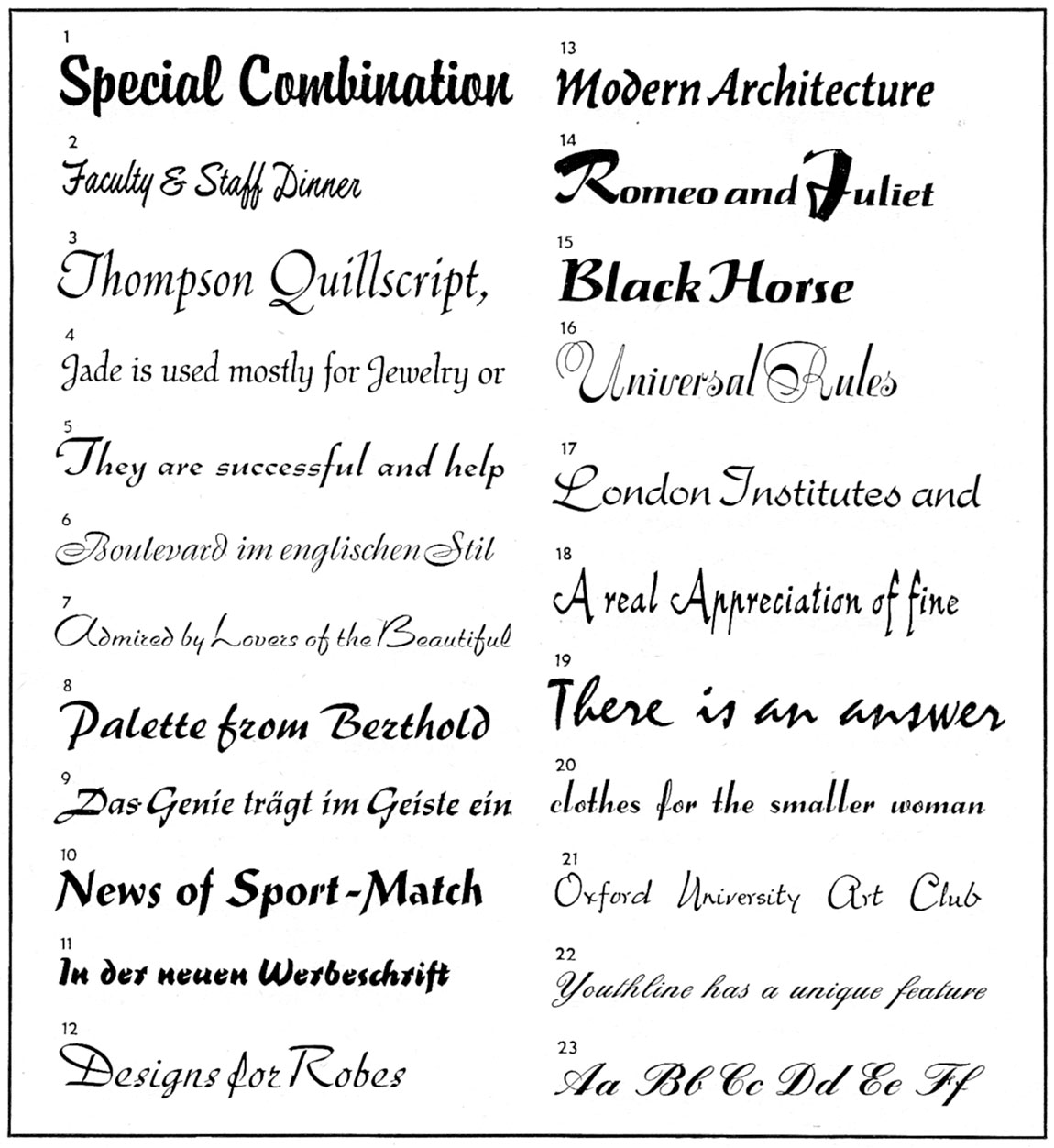

Currently popular script and cursive designs include (1) Brody, (2) Repro Script, (3) Thompson Quillscript, (4) Heritage, (5) Admiral, (6) Boulevard, (7) Caprice, (8) Palette, (9) Derby, (10) Dynamic, (11) Reiner Black, (12) Diskus, (13) Balzac, (14) Salto, (15) Saltino, (16) Stradivarius, (17) Rondo, (18) Reiner Script, (19) Mistral, (20) Mercury Bold, (21) Francesca Ronde, (22) Youthline, and (23) Copperplate Bold.

The famous Stempel foundry, also in Germany, has issued a freely penned cursive called Diskus and and irregular brush letter, Balzac, neither of which will ever have the favor of such Stempel Chancery italics as Palatino and Trajanus.

The German Klingspor foundry lists to designs, Salto and Saltino, which are really one, the difference being only in the capital letters. Salto caps are large and overdrawn while in Saltino caps blend with the lower-case.

The only postwar script from Bauer, best known of the European foundries, is Stradivarius, a cursive with great contrast of stroke, notable for the square effect of the round letters and for the swash capitals. This type is already well-known in America.

Two curses widely accepted here are the Amsterdam Typefoundry types, Rondo and Reiner Script, of which Rondo is the more popular. Amsterdam has recently marketed one of the most unique script types now available—Mistral, cast by Fonderie Olive of Marseille. It is an imitation of ordinary, none-to-regular hand-writing, and definitely distinctive.

Stephenson Blake of Sheffield, England, has for postwar types in this classification. Mercury, available in two weights, is a cursive with flared capitals. Francesca Ronde, a cursive of monotone weight, and to English round hands, Youthline Script, of medium weight, and Copperplate Bold, complete the list.

Of course, the future development of script or cursive types is impossible to forecast. However, it is probable that some of the new forms will not be based upon any particular historic model but will be inspired by hand-lettering styles which are both functional and smart enough to warrant the time and expense of their development.

This article first appeared in the November 1955 issue of The Inland Printer.